By Kent Paterson

A Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) of undetermined sex was captured on camera roaming the back country of the Sierra Madre Occidental in northern Mexico, very precariously. The snapshot was recorded earlier this year on a trap camera in the Campo Verde region of the Chihuahua-Sonora borderlands but not publicized until this month.

According to Mexico’s National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (Conanp), which administers the Campo Verde Natural Protected Area, the photo was considered very significant in that the lobo in question did not possess a GPS collar and was likely the offspring of wolves released in the region under the auspices of the binational Mexico-U.S. Mexican gray wolf reintroduction program.

Conanp reported that the first person who beheld the wolf’s image was a Campo Verde committee member who told the protected area chief of a “strange coyote” photographed by a trap camera while drinking water. Taking a peek, the chief immediately realized that the animal wasn’t a coyote, but its bigger cousin.

Conanp asserted that the thirsty wolf photo showed a “great advance in in the conservation of wolves since it is now possible to speak of the first wild populations in the country after more than five decades.”

In 2021, the Mexican federal government agency calculated that at least 14 wolf litters had been born into the country’s northern wild lands since the beginning of the reintroduction program a decade earlier.

Covering about 280,000 acres, the Campo Verde Natural Protected Area offers suitable habitat for the recovery of the Mexican gray wolf. Mid-range mountainous elevations encompass pine and oak forests, hosting vital wolf prey like the white-tailed deer.

Before U.S.-led extermination campaigns almost drove an apex predator to extinction, the Mexican gray wolf inhabited wide regions of northern and central Mexico, ranging as far south as the southern state of Oaxaca, as well the big swaths of the U.S. Southwest. In Mexico, the Mexican gray wolf is officially classified as an animal in danger of extinction.

Currently, Conanp estimates that 30-35 wild wolves inhabit the Chihuahua-Sonora borderlands, about the same number estimated by Conanp and researcher Carlos López in 2019.

The latest population estimate represents a small number indeed but more than in the 1970s when a handful of the last known wild Mexican wolves was captured and successfully bred to later allow the release of wolves in both the United States and Mexico.

Getting the lead on its southern neighbor, the U.S. reintroduced Mexican gray wolves to the Southwest beginning in 1998; Mexico followed suit starting in 2011.

The U.S. component of the binational program has proven far more successful, with the latest U.S. Fish and Wildlife census numbers (late 2024) estimating at least 286 Mexican gray wolves in Arizona and New Mexico. But in both countries, the canines face highly uncertain futures.

Recovery is seriously jeopardized by illegal killings, vehicle collisions, human-induced climate change and wildfires. U.S. government policy of restricting the presence of Mexican gray wolves to below Interstate 40 and preventing wandering Mexico-origin wolves from staying in the U.S. artificially limits the lobo’s territory.

Although wolf advocates recognize that official binational efforts have brought the Mexican gray wolf back into the wild, they increasingly warn that population fragmentation threatens genetic diversity and long term species survival.

On July 1, Arizona Representative Paul Gosar rolled out the Enhanced Safety for Animals Act (HR 4255), which if approved will delist the Mexican gray wolf from Endangered Species Act protections. According to the Republican Congressman, “Mexican wolves have preyed on cattle, livestock, and even family pets, causing significant financial losses and economic hardship on family-run ranches…”

Wolf conservationists quickly condemned Gosar’s measure, characterizing it as declaring an open season on wolves, especially in Arizona where, unlike New Mexico, no state law gives added protection to the endangered species.

“This bill is a cynical ploy to appease special interests at the expense of the democratic process, public trust and the survival of one of North America’s most endangered mammals,” said Michelle Lute, executive director of Wildlife for All, in a statement signed by representatives of eight other environmental and conservation organizations.

Blocking Cross Border Journeys

Wolves once freely crossed what is now the U.S-Mexico border, but such epic journeys are becoming virtually impossible now with the expansion of U.S. border walls.

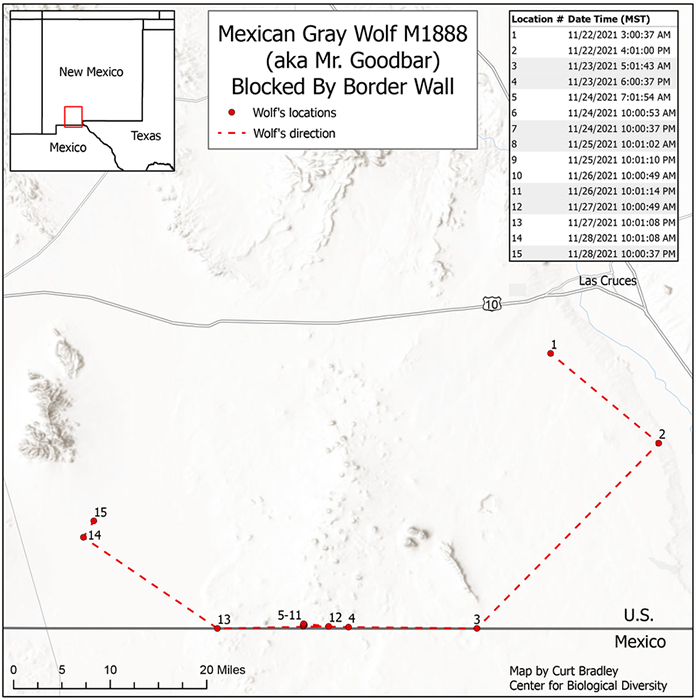

In November 2021, in the first documented instance of how environmentalists’ warnings that border wall construction would impede the movement of migratory creatures, a wolf known as Mr. Goodbar was tracked for several days along 23 miles of the border wall southwest of Las Cruces, an area which is now part of the Trump Administration’s declared National Defense Area.

“Mr. Goodbar’s Thanksgiving was forlorn, since he was thwarted in romancing a female and hunting together for deer and jackrabbits,” Michael Robinson, a senior conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), was quoted at the time. “But beyond one animal’s frustrations, the wall separates wolves in the Southwest from those in Mexico and exacerbates inbreeding in both populations.”

In 2017, two wolves were documented successfully crossing north into the United States from Mexico, one of which roamed around the Paso del Norte borderland before heading back south across the border. According to the CBD, the second wolf was captured and detained by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; that wolf later gave birth to Mr. Goodbar, who was later released into the wild but foiled in his quest to reach an ancestral homeland.

Mr. Goodbar’s truncated trip signaled a streak of bad luck for the hapless wolf, whose story embodies the tragedy yet tenacity of a keystone species imperiled by humans. The male wolf was subsequently found shot but alive in New Mexico, and had to have a leg amputated by a vet at the Albuquerque BioPark before being released back into the wild again where, reportedly, Mr. Goodbar then encountered a possible mate. Hopping around on three legs, the wolf melted back into the wild, wounded but not yet vanquished.