Copper, Turquoise, and Moonshine

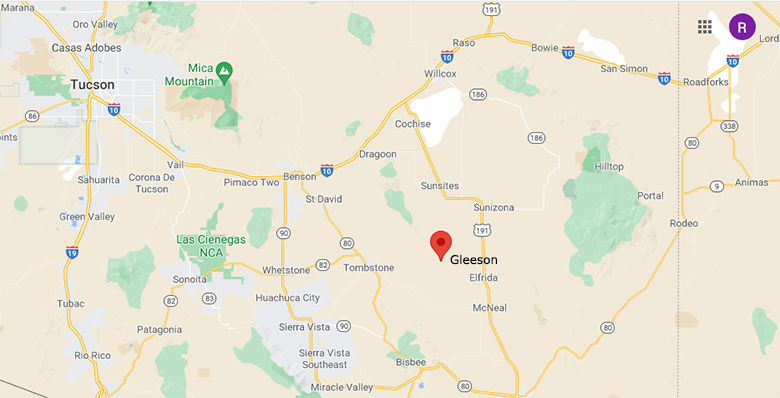

We’ve reached our last stop on the Cochise County Ghost Town Trail: Gleeson, Arizona. When the post office opened in 1890, Gleeson was actually known by the somewhat flashier moniker, Turquoise. You can probably guess why it was called that. In fact, turquoise mining in the area goes back to the Native Americans, who collected the mineral from a mountain known later as…Turquoise Mountain. No less than Tiffany and Co. had bought up the turquoise mines by 1890. But it was copper, lead, and silver that brought most Europeans to the area beginning in the 1870’s.

The post office actually closed for a time in 1900 and when it reopened in 1904 the town had moved a few miles closer to water and was known as Gleeson, after miner and Irishman John Gleeson. Gleeson owned a very productive copper mine and had found the water. While the former attribute might’ve gotten a town named after you in southern Arizona, in this case it was the latter. By this time, Gleeson’s population was about 500.

At first, Gleeson’s main problem was that it kept catching on fire. It burned several times and, on June 7, 1912, the most devastating conflagration incinerated 28 buildings, virtually every structure on both sides of the main street, and was so fast-moving that witnesses believed it had been stoked with oil and matches. While $100,000 in damage had been done, the town was rebuilt and would soldier on for a couple more decades, becoming a bootlegging hot spot when both Arizona and New Mexico banned liquor in 1915 and getting ravaged by the influenza epidemic of 1918.

Later, during federal prohibition, the Musso family, owners of a major mine, were said to have hidden booze below the fish pond in their backyard. In 1980, Philip Varney reported something like a vault below what appeared to be a pond in the back of what remained of the adobe Musso House. I was, sadly, unable to find the place.

Finally, the post office left in 1939 and the last mine shut in 1953.

The most obvious feature left in Gleeson is the jail (above), built in 1910 and an exact duplicate of the one in nearby Courtland. But unlike in the total ghost town of Courtland, after years of neglect a couple residents of Gleeson restored their jail, perhaps because they long ago learned not to take it for granted. An early Gleeson jail had a wooden roof and a criminal quickly broke through and climbed to freedom. The town also had a “jail tree” and for a while wrongdoers were simply chained to it.

One day in January 1917, the Gleeson jail held four barrels of bootleg liquor at imminent risk of being “liberated” by an enterprising citizen who’d already tried to drill a hole through the floor of the railroad freight room where the barrels had been stored. This effort to drain the precious liquid failed when the drilling went wide and the hole in the floor was noticed. Then someone (the same person?) tried to break INTO the jail overnight to get the barrels out. Another failure. The whiskey was poured out in front of the jail the next day.

So, I guess it’s understandable that the Gleeson jail has become something like the town’s focal point. In fact, it now looks downright inviting and is apparently filled with artifacts.

Adjacent to the jail is the old school (above and at top). Philip Varney presents a photo of the pillars flanking the front steps with a narrow, graceful arch connecting them. At some point, the arch clearly fell down but the pillars remain.

The adobe ruins of the hospital (above) are also identifiable, in the hills behind which were the mines. And while the building that housed the Silver Saloon is apparently standing, I couldn’t be certain of its location. Perhaps it’s the building just down the wonderfully named High Lonesome Road. It makes me happy to know that this road has gone by that name since Gleeson’s early days. I guess some things might not change after all.

However, High Lonesome Road is also where Royal Richard Lockett, a 66-year-old butcher, was robbed and murdered in 1913 while on his way by wagon from Gleeson to Courtland to meet the El Paso and Southern. Strangled, stabbed, and then dragged behind his wagon at mid-day by two men near “Dead Mexican Canyon,” a name which would seem to indicate previous trouble in the area, Lockett’s assailants were never found. Tracks in the sand showed that Lockett’s dog had followed the killers for some distance, perhaps evidence that the men were known to both Lockett and his canine companion.

And, on that note, we’ll leave Cochise County. The road west from Gleeson leads right into Tombstone, but The Town Too Tough to Die will have to wait. Next time we’ll travel way up north to I-40 and visit the neighbor of Two Guns, Twin Arrows.

For more information on the Ghost Town Trail of Cochise County, visit the official website. That’s where I got a lot of information about Gleeson for this post. Gleeson has its own web page with links to stories on bootlegging and influenza in Gleeson, as well as the sad story of Royal Richard Lockett. The Gleeson Jail also has its own page and is open the 1st Saturday of each month and by appointment. Unfortunately, I did not know that until recently. As usual, Philip Varney is worth having a look at, too.

City of Dust creator John Mulhouse’s new book, “Abandoned New Mexico: Ghost Towns, Endangered Architecture, and Hidden History,” published by Fonthill Media, is now available at: https://cityofdust.bigcartel.com/.