This post originally appeared on June 6, 2012.

I went to my favorite bar last week.

I walked over. The international pedestrian bridges are in the last stages of a makeover. I bought a chit from a vending machine at the pedestrian plaza and swiped it at an automated gate, which whooshed open just like on Star Trek. The American side of the bridge is covered by an expanded steel half-arch. The Mexican side is still covered by nylon tarp over chain link fence. For years, the Mexicans’ simple accommodations made their side more comfortable for pedestrians, but the wheels of American bureaucracy have now caught up.

The Cucaracha is twilight dark, and mostly empty all the time. Roberto, the bartender/owner, usually sits at the far end of the bar, watching, on a fifteen inch television with built-in VHS, satellite broadcasts in English and Spanish, and tapes of Masterpiece Theater, and occasionally some kinky Russian porn with models in lab coats.

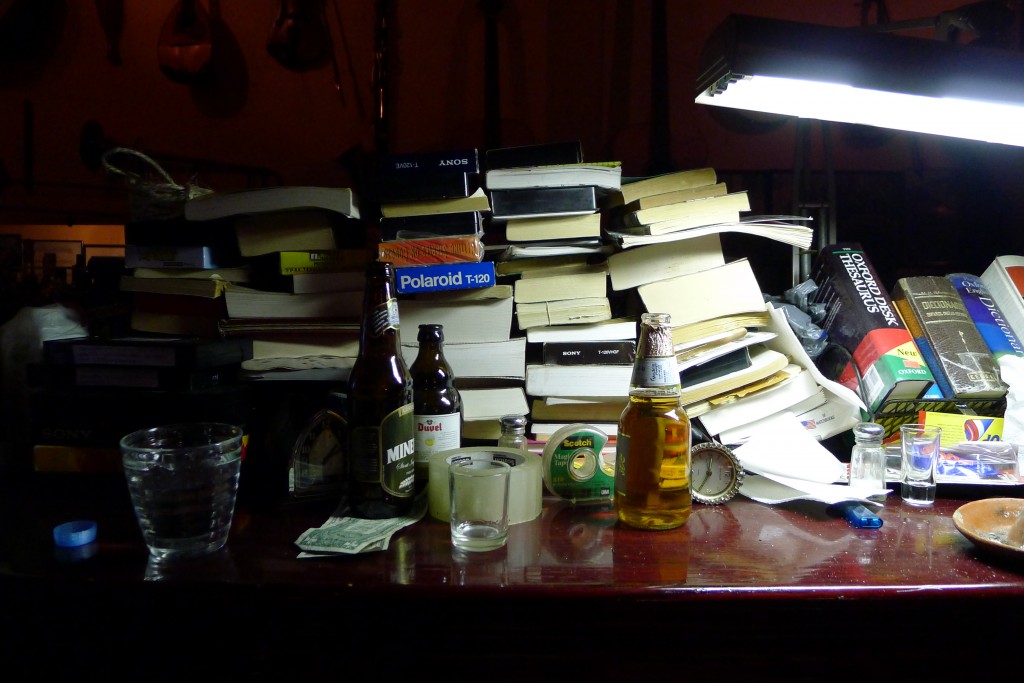

The Cucaracha is as deep as the block. A tacos and burger joint was carved out of the street frontage, so a wide hallway leads to the bar. The clutter starts at the back, and has slowly accreted into the usable area. Books and videotapes are stacked on the bar, and the stairway to the disused second floor is lined with cardboard boxes. Customers come infrequently to the Cucaracha, and keeping the place tidy must seem like a waste of time. When I visit, I’m usually the only client the whole time I’m there.

Roberto is a collector and a connoisseur. He shops the pawn shops and flea markets in Juarez frequently. He says that as the Juarez economy tanked, the buys improved. Musical instruments hang from the walls, among them an acoustic bass and a classical guitar and clarinets and saxophones. Looking at them I wish I could bring a bluegrass or Klezmer band in to take the instruments off the wall and give an impromptu concert. Old radios line the top of one upright piano, and another upright piano holds objets d’ arte nouveau.

The back bar as well reflects Roberto’s connoisseurship. Roberto prefers robust spirits. Behind the bar he keeps bottles of rum, including Cuban rums forbidden in the United States. He also makes macerations with fruit, and a tincture of Chuchupaste, the Raramuri medicinal root.

But last week he had Sotol. And that’s why I went. Two weeks ago I stopped by, and he told me that he’d bought five liters each of silver and yellow Sotols from some guys who showed up selling it. He called the yellow Sotol citrine, and I had to ask him what it meant. It came from Durango, they said.

You wouldn’t think that Sotol would be hard to find in Juarez, but mostly it’s scarce. For Mexicans, Sotol is a poor man’s drink. Mexicans prefer Presidente, or Buchanan’s, or maybe Herradura. Some grocery stores stock Sotol Coyamito, but the distillers of Coyamito facilitate the alcohol production by adding 20 kilo bags of table sugar to their hot-tub-size cement fermentation tanks. Sugar alcohol gives me a headache.

And getting Sotol into the usual distribution channels is hard in Mexico, because in small towns, where most of the Sotol distilleries are, the distillers compete directly with the liquor stores for the retail dollar. In the United States, we are saddled with a three-tier system, an archaic holdover from the days immediately following Prohibition. Under the three-tier system, distillers can only sell to wholesalers, who sell to retailers, who sell to consumers. Ostensibly, the system is in place to keep criminals out. Functionally, it eliminates anyone without boatloads of cash. Mexico, sensibly, is more wide open. In Mexico, you can go to the distillery and fill your empty coke bottle right from the still, like taking your olla to the restaurant for menudo.

So last week, I went back, to drink more Sotol, while it’s still relatively easily attainable, in a bar just over the bridge.

I sat at the bar and drank Sotol and bottled water. Roberto and I talked politics of the northern variety. Has he always been Beto? he asked me.

Roberto cleared some museum-quality art books off the pool table. I racked, and we played eight-ball, and I couldn’t make a shot, so I drank more Sotol, and racked for some nine-ball.

A couple of guys came in and sat at the bar. They were dressed nice enough, in blue jeans and button shirts. Maybe a little too nice. They ordered a couple of Clamatos, and sat at the bar while Roberto mixed the virgin drinks and I kept shooting.

I left Roberto with an easy run, but he muffed the eight ball. I dropped the eight, but blew the nine, and Roberto sank it.

The guys paid their tab, and stood up to leave.

How’s business? the older one asked.

Like this, Roberto said, referring to the nearly empty bar.

But on the weekends?

Jodido.

After they left, Roberto asked me What did you think of those guys?

I dunno.

They looked like criminals to me.

I was thinking the same thing, I told him.

We sat, for a while, in silence. He rolled a cigarette, and lit it.

Maybe they were in the army, I offered.

No. Too fat.

I drank another shot of Sotol, and paid my tab. I, at least, had the option of going home.

Rich Wright

Nice vignette. Makes me want to visit Juarez again after a long time.

My first sotol was in Madera, from an old rum bottle. It was clear. Like drinking kerosene!

But I agree, your story makes me miss my Mexican ramblings.

There’s a Sotolero in Madera called Gato, but I’ve never tried his sauce. The Fernandez Brothers make some hooch in Madera, also, and they call it Sotol, but really it’s made with some undetermined agave (undetermined by me, at least).

Sotol really changes as it ages. Bottle conditioning, spirits experts call it. (The term aging refers to barreled spirits.) You may have gotten some Sotol the same day it was bottled.