by Bob Chessey

El Paso’s First Career Customs Inspectress

When crossing an international bridge from Juarez to enter El Paso, we take for granted that the Custom Inspectors evaluating, questioning, and, if necessary, searching arrivals, will include both men and women inspectors. Historically, the presence of women inspectors at the El Paso international bridges maintained a checkered on again/off again status.

As early as the 1890’s the US Customs Service at the El Paso Port of Entry had inconsistently employed a female Inspector to confront women suspected of concealing contraband beneath their clothing. Thirty years later, after Pascual Orozco had revolted against Mexican President Francisco Madero in 1912, there was a surge in munition smuggling from El Paso into Juarez. Initially the search of all people and cargo crossing the bridges into Juarez had been conducted by US military personnel. In May of that year US federal agent Louis Ross of the local bureau of investigation (legacy agency of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or FBI), reported that Orozco’s army was receiving an average of 1,000 ammunition rounds a day in clandestine deliveries. Most of the bullets were carried across the border in small amounts that had been concealed inside the clothing of women, most of whom were Mexican, who would flood across the border in large numbers aboard the streetcars that crossed the Stanton Street bridge into Juarez. Because the ammunition presented an overt threat to their government, Mexico funded the hiring of several American inspectresses to search suspected female smugglers. Notably, these searches focused on women departing, and not entering, the United States.

Hardly surprising, the searches agitated the Mexican women who would often physically lash out by scratching and slapping the inspectresses. The local bureau justified their new employees’ actions and the accompanying tension by declaring that ammunition smuggling had declined and assurances that no women’s clothing was removed during the searches. Nonetheless, avoiding the scrutiny of the inspectresses took minimal effort as they were only on duty four hours a day.

By June there was only a single inspectress responsible for the Stanton Street and the Santa Fe Street bridges as well as the footbridge across the Rio Grande located below the smelter. Two of Ross’s informants told him that the footbridge was a heavily trafficked smuggling route and that they had estimated 30-40 Mexican women crossed daily carrying a combined total of between two to three thousand rounds of ammunition. To combat this porous hot spot, Agent Ross requested additional funding to hire more inspectresses but had trouble securing the necessary money. Eventually the positions again were funded by the Mexican government, securing Ross the means to hire two new inspectresses who worked from 6 a. m. to midnight in two shifts of nine hours each. Their salaries were $3 a day ($93.33 in 2022).

The inspectresses hired that summer had been a stop gap measure financed by the Mexican government. After August 23, 1912, the position of “inspectress” at the international bridges in El Paso were eliminated.

In 1923, Nell Da Costa accepted the position of Custom Inspectress at the Santa Fe Bridge and for years was employed as the sole female inspector. Da Costa holds the distinction of being the first woman to be hired as a Custom Inspectress in El Paso and hold the position until retirement.

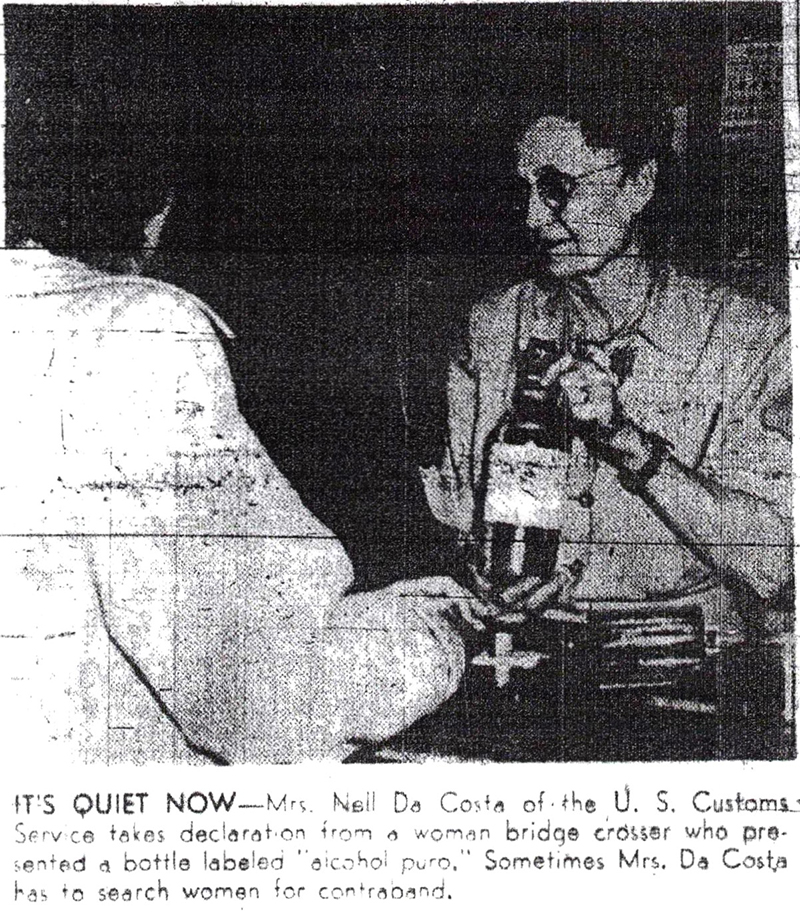

On February 16, 1923, 41-year-old Nell M. Da Costa, who stood five foot seven inches and weighed 133 lbs., transferred from her position as Matron for the US Immigration Service, to employment as an Inspectress for US Customs. The new job responsibilities included typing reports, keeping index of seizures, issuing customs forms, taking phone calls for both the Agriculture and Customs Inspectors, and maintaining an index file of pertinent purchases from Mexico.

But the primary responsibility carried by Ms. Da Costa was to search female travelers who were suspected of hiding contraband on their person. To fulfill these duties the Inspectress worked a grueling schedule, “As Inspectress at the Santa Fe St Bridge, El Paso, Texas, I am subject to call at all hours and night work as the occasion demands, and my duties consist of searching female passengers suspected of having smuggled goods, narcotics, contraband and merchandise concealed on their person.”

A supervisor elaborated, “Mrs. Da Costa works an 8-hour shift, sometimes in the morning and sometimes at night, in charge of the examination of women suspected of having contraband merchandise concealed on the (sic) persons. Works 7 days per week, but has one day off in every nine, compensator (sic).”

Many of the women who were suspected of concealing prohibited items had no intention of being searched and were determined not to cooperate. As a result, it was not uncommon for this belligerent attitude to erupt into violent clashes with Da Costa. In 1951 the veteran Inspectress recalled her early years during the Prohibition era, “The border was rough, and I didn’t dare go to work, especially at night, without a gun. I’d keep it in my desk at the office. I used to have big fights with women who tried to resist being searched. Of course, I didn’t use my gun on them. I fought back,” she said. “I got my eyes blacked and my wrist and fingers broken… People would do anything to get liquor.” She then sighed, and thirty years after that lawless period the seasoned Custom official realized, “You know, I haven’t had a fight in a long time.”

Da Costa’s ability to hold her ground during these physical confrontations led her colleagues to christen the battle-hardened Inspectress, “Salty Nell.”

Females who were suspected of concealing proscribed items would be taken from the primary inspection area, escorted across the street, and directed into Ms. Da Costa’s one-room shack and be searched, some forcibly. One particular encounter left an indelible memory on the Inspectress, “You might think that a woman couldn’t conceal much liquor about her person, but I searched a woman who had any quantity of it on her. She was wearing a sort of harness filled with bottles. The affair wasn’t built for walking, and she was driving a car. When she walked into the office to be searched, the bottles clinked and knocked together. You could have heard her a mile off.”

In 1929 officers working the bridges in El Paso discovered a new method favored by women planning to sneak liquor into the US, strapping hip pocket flasks to their legs underneath their skirts and dresses. The local press speculated, “the inspectress at the Santa Fe bridge will be kept very busy until the fad is passe. The week that prediction was published Da Costa already had taken into custody two women wearing a harness under their dresses, each concealing six pints of whiskey.

The desire to quench a forbidden thirst was not restricted to people outside of government employment. Less than four months after assuming her position with Customs, Da Costa was assigned to conduct a secondary inspection of a woman who had been removed from a street car returning from Juarez and had been escorted by a male immigration officer to the female inspector’s shack. The inspectress described what followed, “An immigration officer brought a woman to my quarters asking me to search her. When I attempted to do so she cursed me and threatened to hit me with a fire shovel if I further searched her after taking aguacates (avocados) from the pocket of her dress and cigarets (14 packages) from under her arm. However, I did search her, and in taking a bottle (half pint of whisky) concealed in the front of her clothes, she twisted my arm and tried to hit me with her fist.”

When confronted with her confiscated contraband, the woman became indignant and protested to officials that she held a public office in Los Angeles County, California, and had traveled to El Paso transporting two mentally ill women. This disclosure initiated a conference between officials of the Treasury Department and Assistant United States District Attorney N. J. Morrison, who decided that the incident should be reported to the smuggler’s superior officers; the woman was released and allowed to return to Los Angeles.

Six years later Salty Nell drolly summed up the altercation, “That was almost too exciting.”

Alcoholic beverages were not the only contraband sought and discovered during the Inspectress’ years of service; narcotics remained a continuous challenge. In 1929, drawing upon several years of acquired experience, Da Costa shared her gained insight, “You can’t judge a person smuggling dope by her appearance. Some of the most mild and innocent looking women will do the most unexpected things. Men leave the room here (in the “shack” where Da Costa searched women), and I pull down the shades and search women suspects. Sometimes women who are alone with me try to escape.

“Some women have the most innocent expressions. One would never suspect them, and then they turn out to be wild cats. I found some dope on a young American (Anglo) girl. She tried to jump out of the window. She broke the window with her hand, and tore down the shade. I caught her hand and then she bit me. She bit my hand so hard that she crushed the bone, and I thought my thumb was broken.

“She threw the dope out of the window, where it was found by an inspector. She was pretty, nice and sweet, and there was something about her that was appealing. She seemed like a corner rabbit (docile person).”

Years of performing searches at the bridge had proven that narcotic smuggling was not the sole domain of the young, “Some old women with white hair smuggle dope. I searched one woman and found dope hidden in her long hair.

A second memorable search was of a sweet appearing elderly woman who had assured “Salty Nell” that she held nothing illegal in her possession. Da Costa recalled trying to calm her, “’I don’t suppose you have.’ But she looked so nice I didn’t want to hurt her feelings. But let me see anyhow,’ I said. And then she hit me. She hit me so hard she knocked me down and I fell against the corner of the desk. I had black and blue marks for weeks where she hit me and where I bounced against the desk. She had her dope tied up in a bandanna handkerchief, and she tried to get the handkerchief untied so she could swallow the evidence.

“(Co-worker) Inspector Frank Logan came in just then, and she tried to swallow handkerchief and all. He helped me or I don’t know what would have happened. We got her quiet somehow, and she didn’t swallow (the) handkerchief, dope and all. But I wouldn’t want to go through the affair again. I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I hadn’t had help.”

Having personally searched hundreds, if not thousands of women crossing the international bridge, Da Costa had discovered narcotics secreted in inventive locations including, the soles of shoes; teeth cavities; and, in cases where a smuggler feared a search could be ordered, narcotic filled finger stalls placed in their mouths to be swallowed. Also used in attempts to foil the scrutinizing eyes of the Custom Inspectress was feminine clothing, contraband had been masked in falsies, corsets and girdles.

In the early 1950’s, when an aftosa (foot and mouth disease) quarantine was in effect, one search beneath a woman’s clothing revealed a peculiar contraband. During the search Da Costa uncovered, strapped taut around the woman’s waist, a girdle of beefsteaks.

Unfortunately, El Paso’s lone female custom officer exhibited racist beliefs and attitude toward some of the people she had been hired to interact with and search. On an official form dated September of 1928, Da Costa penned her perception of many of the women she examined, “The class of persons dealt with are not of the highest type—often ignorant, filthy and diseased Mexicans and rough, tough characters of other nationalities who sometimes threaten, curse or attack me.”

Expressions of her racist beliefs were not confined within the framework of bureaucratic paperwork. One year later Da Costa described to a reporter a woman who warranted a search, “Another time an old negro mammy that looked as sweet as the Aunt Jemima pancake ads came in to be searched.”

The same month “Salty Nell” turned 70 years of age, after having endured 28 years of typing, filing, inclement weather, repetitious smart-ass answers to inquiries that everyone believed were original, verbal insults, breathing car fumes, mumbled threats, physical assaults, long hours with swollen feet, and being on-call, in September 1951, the veteran inspectress retired from the US Customs Service. As she approached retirement Da Costa aptly boasted, “There are not many places women can hide contraband that I don’t know about. After 30 years I can almost look at them and tell whether they’re guilty”.

“Salty Nell” Da Costa, the forgotten connection between the women who originally worked at El Paso’s international bridges on a sporadic and short-term basis to the current career female Custom Inspectors at El Paso’s Ports of Entry, died December 20, 1965, and is buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery.

“Salty Nell’s” legacy was captured by an El Paso Herald Post reporter who posited, based on a mixture of fact and hyperbole, that during her groundbreaking career Da Costa had searched more women smugglers than anybody else on earth.

Except as noted, all photos are from the collection of the author.

Sigh on ugly history in the borderlands. I will send this to my co-author; we wrote an article about cavity searches as late as 2013. A woman, not carrying drug contraband in her female ‘cavity’, was taken to UMC, did not consent to the tech intrusion, and then was billed for >$5k.

She settled with UMC for $1.1 million.

I am not sure why you posted this Rich. Sounds very Racist to me, ONLY searching “Mexican” women as if Anglos and Gabachos didn’t smuggle alcohol into the US? My Armenian Grandfather owned Curley’s Club on Avenida Juarez for over 40 years…..and he sure sold alot of booze to Gringo’s. What’s up next? How the El Paso Jailers “accidentally” dropped a match on the “Mexicans” being deloused with gasoline?

Let’s look at it in the historical context. The United States was a racist country, and, to a large extent, continues to be racist.

Don’t shoot the messenger.

That’s only your take on this piece, Devin+. I would say that this is simply reflective of a time when just such attitudes prevailed, and denying or ignoring history is never a good idea. And, there is no mention of “ONLY” searching any one type of female. I find it interesting, and still believe we all need to acknowledge this reality of our past.