By Kent Paterson

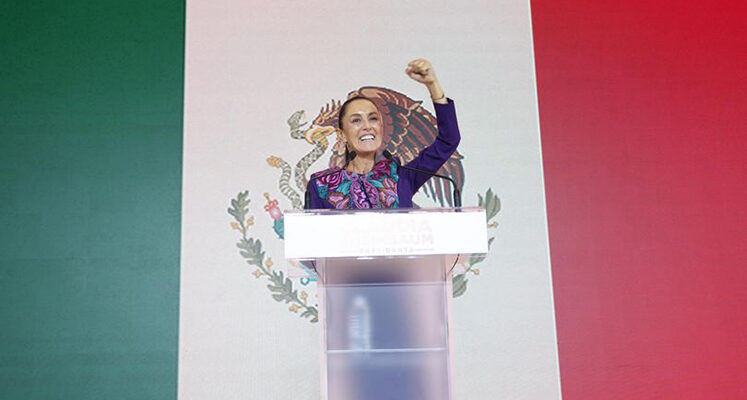

Appropriately dubbed the “Time of Women,” the 2024 Mexican elections ushered in the first woman elected as president in Mexico’s 214-year history. On October 1, Claudia Sheinbaum will assume the country’s highest office, succeeding her longtime political colleague Andres Manuel López Obrador.

A onetime student activist, former Mexico City governor and member of the Nobel-winning 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, among other qualities, Sheinbaum is a dedicated co-crafter of and enthusiastic adherent to outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s Fourth Transformation program of social, political and economic reform known as the 4T.

Like López Obrador, president-elect Sheinbaum vows to continue with the 4T’s landmark social programs, including its universal senior pensions. What’s more, she pledges to extend the 4T to a “second level” while governing in the interests of all Mexicans, not just the privileged few.

In post-election day remarks, Sheinbaum, who turns 62 this month, celebrated her June 2 landslide victory as a collective triumph for Mexican women, who’ve steadily gained positions of political power during the last two decades.

“Women have arrived at the highest distinction that our people could give us-the presidency of Mexico,” Sheinbaum said. “I say this in the plural, because as I said, I don’t come alone-we all do.”

Mario Delgado, chief of Sheinbaum’s Morena party, lauded his candidate’s win as not only a gender milestone for Mexico, but for North America as well. Now it’s up to Canada and the United States to catch up with Mexico and one day elect female heads of state.

Sheinbaum’s landslide victory of 33 million plus votes, or nearly 60 percent of the total ballots cast, is the most votes ever received by a presidential candidate in Mexico, even surpassing López Obrador’s own win with 30 million votes in 2018.

But the electoral landslide wasn’t just confined to the presidential contest. With more than 20,000 political posts up for grabs across the nation, Mexico’s biggest election ever, the preliminary election tallies show Sheinbaum’s three-party electoral coalition, made up of the Morena, Labor and Mexican Green parties, gaining 372 seats in the lower house of Congress and electing 83 senators. The results have the coalition just two Senate votes shy in possessing the necessary votes to pass constitutional reforms.

The new Mexican Congress will first convene September 1, one month before Sheinbaum takes office.

Sheinbaum’s landslide likewise translated into the coalition’s dominance of state governorships and legislatures that were up for a vote on June 2. Crucially, the future president will enjoy great political clout in expanding the 4T’s healthcare and other programs into the grassroots.

According to Interior Minister Luisa María Alcalde Luján, a total of 59,987,000 Mexicans cast ballots on June 2, or nearly 61 percent of registered voters. Despite the overwhelming wins for Morena and its allies, opposition candidates are expected to file legal challenges in a bid to delegitimize the elections. Given the landslide results, the opposition faces quite a heavy lift.

Election Day in Juarez

Election day ’24 in Ciudad Juárez proceeded amidst a general atmosphere of tranquility, save for a few reports of alleged vote buying and voting problems at some precincts. Interspersed with spring winds, a hot day set in early. In downtown Juárez, far fewer shoppers and street vendors were visibly present than usual and the bars on Avenida Juárez stood shuttered per the election dry law that went into effect Saturday afternoon through one minute before midnight Sunday.

The usually bustling Del Rio convenience store just down the Avenida from the Santa Fe Bridge was nearly empty Sunday morning, plastered with signs across the beer fridges announcing the temporary no-alcohol sales rule.

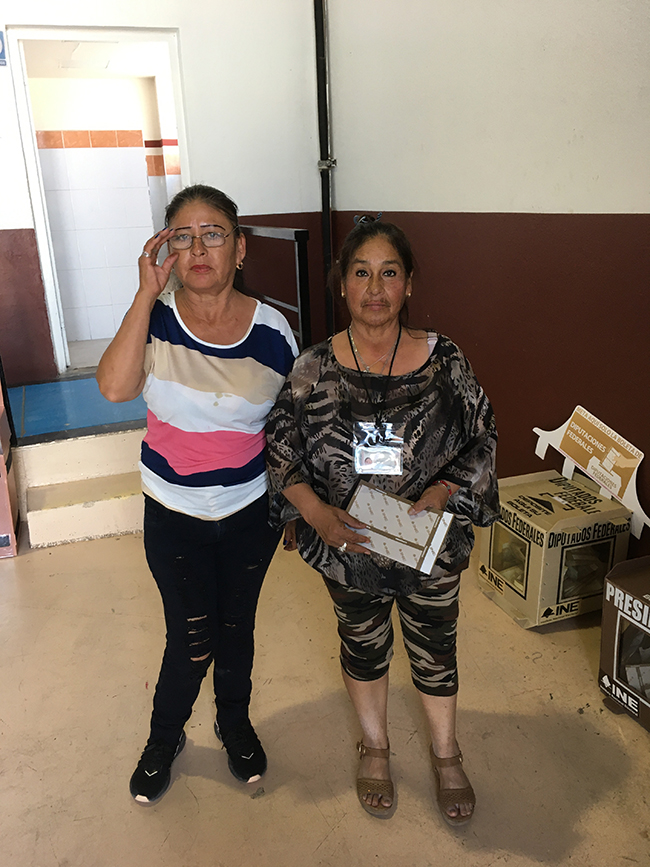

On the edge of the Bella Vista neighborhood, a pair of dogs snoozed in the shade outside the election precinct inside the Josué Neri Santos Gymnasium across from Juan Gabriel Plaza. Election workers said the morning voting was slow but expected to pick up in the afternoon.

At another precinct located inside the Municipal Women’s Institute fronting the railroad tracks that divide Avenida Francisco Villa, election workers also sat at tables waiting for voters. Several people entered inquiring about voting, but were turned away because they were out-of-towners not registered on the local voter rolls. Precinct staff then directed the interested voters to special precincts legally established to serve traveling citizens on election day.

The special precincts witness heavy human traffic in tourism-oriented and border cities where floating and migrant populations abound. Luis Valencia of Las Cruces, New Mexico, was among the unhappy travelers searching for a place to vote in Juárez.

According to Valencia, a Spanish-language radio broadcaster on an FM station heard in Las Cruces informed listeners that eligible Mexican voters on the U.S. side of the border could cast their presidential ballot at the Mexican Consulate in El Paso. But Valencia and others soon discovered that was not the case; the consulate posted a sign on its doors that interested persons could vote at other specifically designated consulates, the nearest ones located in Phoenix, Dallas and Houston.

In an effort to expand the absentee vote, the National Electoral Institute (INE) and Mexican federal government accredited 23 consulates in the U.S. and other nations to administer in-person voting, but El Paso wasn’t one of them.

“Many Mexicans who live in Las Cruces are mad because they don’t have money to travel (to vote),” Valencia told this reporter. “I have a responsibility to vote because if I don’t vote, what right do I have to give an opinion?”

A frustrated Valencia said he would contact a ride platform service to take him to one of the special precincts in Juárez suggested by the precinct staff.

Predictably, problems were soon reported by local media at some of the special precincts in Juarez when the number of people trying to vote exceeded the quantity of special ballots, which are limited by law to 1,000 ballots per special precinct, an increase from 750 ballots authorized during previous elections. The ballot shortage problem is far from new, and is a recurrent source of conflicts and complaints which have been documented in every Mexican presidential election covered by this reporter since 2000.

Fearing a proliferation of surplus ballots that could be fraudulently used, lawmakers from all the political parties have been reluctant to authorize significantly higher numbers of ballots for the special precincts. But Mexico is a country and people in movement, and every election cycle otherwise eligible voters who are away from home are turned away from special precincts because of ballot shortages. It’s unclear how many people in Juárez couldn’t vote this June 2 at the 12 special precincts set up in the city due to the lack of ballots.

Nonetheless, certain progress- albeit very slow- has been realized in recent years in implementing the right of Mexicans living or traveling abroad to vote in their country’s presidential election.

While 32,621 Mexicans voted from abroad in 2006, the number increased to 40, 714 in 2012 and then 98,470 in 2018, according to BBVA research.

Speaking at López Obrador’s morning press conference of June 3, Interior Minister Luisa María Alcalde reported 197,203 such votes were cast in the 2024 election, whether via the web, postal services or in person at the 23 designated consulates in the U.S. and other nations.

Overall, the percentage of Mexicans abroad participating in presidential elections is still very small considering that millions are of voting age.

Trends, Tattoos and Taps for the Right

Back in the Paso del Norte borderland, another rising figure from Mexico’s burgeoning cadre of women politicians, 27-year Morena Congresswoman Andrea Chávez of Ciudad Juárez, won a Senate seat, while the city’s mayor, Cruz Perez Cuellar, won reelection on the Morena ticket, beating out four rivals.

A candidate with virtually no resources, 26-year-old Jaime Flores of the fledgling People’s Party, injected culture and color into the mayoral race. A self-proclaimed social revolutionary, rapper and YouTuber who was raised by a working-class mom in the poor neighborhood of Rancho Anapra bordering Sunland Park, the heavily-tattooed Flores told Milenio news that listening to the incendiary Mexican musical group Molotov when he was 13 spurred his interest in politics. Flores obtained 16.661 votes, representing 5.98 of the total cast in the mayoral race, according to the news site LaVerdadJuarez.com

Long-entrenched in Chihuahua, the conservative National Action Party (PAN) still has the border state’s governorship, which wasn’t up for election this round, in the person of María Eugenia Campos Galván, aka Maru. Contemporary political trends bode deathly ill for the PAN but refreshingly life-giving for Morena and the electoral left.

Nationwide, the center-right opposition and its woman candidate, Xóchitl Gálvez, failed to provide a coherent and convincing alternative to the 4T. “The results are for all to see,” editorialized left-leaning La Jornada daily. “The political representatives of the neo-liberal right and oligarchy, their intellectuals and pundits and their ‘civil’ front organizations are now living a profound and irreparable defeat.”

Though enjoying a renewed mandate for advancing the 4T’s agenda, Claudia Sheinbaum confronts a host of thorny problems in consolidating the emerging new social pact between the Mexican State and people, underpinned by what López Obrador and Sheinbaum call Mexican Humanism.

A short list of pitfalls includes social spending vs. budget deficits, revenue shortfalls, sticky inflation similar to north of the border, an arguable overdependence on U.S. markets, persistent criminal and gender violence, and migration crises sprouting in other nations but affecting Mexico as THE route of transit to the U.S. Guns and bullets still flow from El Norte.

In foreign relations, Sheinbaum vows to continue a “respectful” and friendly relationship with the United States, while maintaining the López Obrador administration’s policies of non-intervention in the affairs of other nations and differences with Washington over diplomatic and economic relationships with Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela. A return of Donald Trump to the White House could spell trouble for Mexico and President Sheinbaum.

Rated one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change, Mexico’s mounting ecological crises, evidenced by last year’s hurricane that devastated Acapulco, deadly heat waves this year, and growing water shortages across the nation, will seriously test Sheinbaum’s environmental credentials.

Critics of the Mexican president elect sometimes accuse her of being a simple stooge of López Obrador, who they insist will remain the real power behind the throne after he formally leaves office. But as no less a radical than Tony Garza, former U.S. Ambassador to Mexico and business consultant, observed in his most recent e-newsletter, “..we should be skeptical of pundits’ conclusions that she will simply follow in the shadow of her predecessor.”

The Essence of the 2024 Vote

For months, Claudia Sheinbaum was clearly the front-runner in most serious Mexican polls. U.S. and Mexican media outlets, however, largely missed seeing what was happening on the big boat that ferried her to the shores of victory.

Foreign and national media coverage of the June 2 election campaign focused on ongoing criminal violence, the murders of dozens of mostly local and state candidates in several regions of Mexico, the unsolved murders and disappearances of tens of thousands of other people, possible but unproven infiltration of organized crime in political races, perceived or real shortcomings of the 4T, widening gaps between the rich and the poor (as in the U.S.?), and the supposed authoritarianism of the federal government. In sum, a nation teetering on the brink of disaster.

Logically, if such heady issues were decisive factors for the majority of voters, the opposition would have prevailed or at least not been buried in a landslide.

But for masses of Mexicans, López Obrador’s administration (and by extension Sheinbaum’s candidacy) is the first time any government truly spoke their language and paid attention to their needs, delivering tangible benefits in the form of senior pensions, student grants, rural support programs, and more.

Ciudad Juárez author and book seller Antonio Chávez summed up the popular sentiment heard on the streets: “I’m 70 years old and I’ve never gotten a nickel from the government. I get 6,000 pesos every month ( 4T senior pension)…it helps me pay rent.”

Problems and pandemics aside, the Mexico of the Fourth Transformation has been a time of real wage hikes, new space for independent unions and a little more spending money to spread around town. Here, the old U.S. political adage could apply in positive fashion: “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Still, the 4T cuts deeper than narrow individual benefits. History will obviously judge López Obrador’s controversial mega-projects, but many Mexicans are now proud to have a new airport outside Mexico City, passenger train service available or on the planning board, a new oil refinery built, reasonably stable gasoline prices, a network of new state-owned banks, several new universities, and a revamped health system rolling out except in the handful of states still controlled by the opposition.

From the President’s official website

Whatever his shortcomings, López Obrador’s daily televised Mexican history lessons and cutting criticisms against elites, corrupt politicians and repressive rulers strike meaningful chords with the masses who’ve survived decades of scandal, economic deprivation and violent subjugation. For many, the outgoing president’s philosophical principle of “For the well-being of all, first the poor,” are not the empty words of the latest pretender to a satin-laced throne. All this is the mantle Claudia Sheinbaum will inherit on October 1, and if the winds of history keep blowing her way, she may well carve an even bigger and better one to pass on to others.

As a PhD level environmental scientist, I hope she intervenes to enable discussions on shared aquifers along the US-Mexico border. These have been mapped and some modeled but good data is scarce. Current treaties address surface water, especially the 1944 treaty, but groundwater is lost because it is invisible. And, it is becoming more important as climate change dries up surface water resources. The Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Program is designed to produce the data for this. It is working on a limited number of aquifers to get people (typically academics) on the same page as to the status of the groundwater in the aquifer. It is not along the whole border and California opted out of participating on the US side.

This is an issue that is right here at home because El Paso and Juarez have their “straws” stuck into the same aquifer, the Hueco Bolson.

Agua Prieta, Sonora

Kent: Thanks for your piece about the election. As someone who is continually being told that I “drank the AMLO koolaid”, the points you make ring true to me and what I have learned by living here for the past 37 years. I will continue to listen to AMLO every morning and will miss his daily history lessons come September.

K