By Kent Paterson

Photos by Kent Paterson

For years, residents of El Paso’s south-central Chamizal area have waged battles against pollution and public health threats, including hazards stemming from a commercial rail yard, toxic waste from an old recycling plant, fires from a cardboard processing facility, and constant emissions from an endless stream of cars, buses and trucks that rumble along local roadways and in and out of the Bridge of the Americas (aka the “Free Bridge” due to its toll-free passage) that connects with neighboring Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

Overall, the lives of Chamizal’s working-class and mainly Chicano/a and Mexicano/a residents are marked by buffer-free train tracks, fast-moving vehicular corridors, and a high volume border trade that whisks past their homes for the consumption of others far away.

Now, however, community activists and residents are celebrating a bit of positive news. Augurs of a possible new future were witnessed October 24 during a visit of Dr. Earthea Nance of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), who announced a $500,000 grant for air quality monitoring focused on the Chamizal.

Funded by the Biden Administration’s American Rescue Plan, the grant was awarded to La Mujer Obrera (LMO), a longtime community and labor activist organization based in the Chamizal.

According to representatives of LMO and the closely allied Familias Unidas de Chamizal, the funding will allow the grantees to conduct air quality monitoring and develop a community action plan that will put families and public health first.

“It’s going help us show that there is an issue there…,” said Hilda Villegas, spokesperson for Familias Unidas de Chamizal.

In addition to collecting relevant data on air pollution, the plan could lay the groundwork for stricter regulations, federal resources for pollution mitigation, community education, and greater involvement from government agencies in protecting children’s health from environmental risks, Villegas added.

“It’s how we develop a plan that’s really going to tackle all the different things,” she said. “And it’s not just one solution, it’s numerous, and so that’s what we hope to be able to do. It’s a multi-component plan, but the most important thing is that the plan is going to be led by the community.”

In a statement, the EPA said the $500,000 grant is designed to be a multi-year study with the project ending in 2027. The funding will allow the grantees to document air pollution emissions block-by-block and establish two stationary air monitoring stations, with the locations to be determined, in addition to mobile monitoring.

After enjoying a luncheon at La Mujer Obrera’s Texas Avenue headquarters, community members and officials hopped aboard a small bus for a “toxic tour” of the Chamizal area that included stops at a commercial train yard, the W. Silver recycling operation and a pedestrian overpass, among other sites.

Tour participants walked along train tracks that snake through the Chamizal close to residences and which have residents very concerned not only about accidents and dangers posed by the shipment of hazardous materials, but the safety of small children who might even play on the unfenced tracks as well.

“We’ve seen in the news multiple train explosions, and this (railway) is just as dangerous with the contaminants that travel on these trains. They’re not just putting the Chamizal community in danger but a 10-mile radius both ways,” contended Cemelli de Aztlan of La Mujer Obrera and Familias Unidas de Chamizal.

Continuing on their journey through the community, tour participants halted for a street side presentation outside Douglas Elementary School and across from a residential complex.

“When UT Austin did a study about our zoning in Barrio Chamizal, they were horrified to see how close and zigzagged we are as a residential with dangerous industrial zones,” Cemelli de Aztlan said.

In a short history lesson, she described how race, class and politics shape socio-environmental landscapes and living conditions, reminding her listeners that the old school was once a segregated institution during the time the Ku Klux Klan controlled the El Paso school board in the early 1920s.

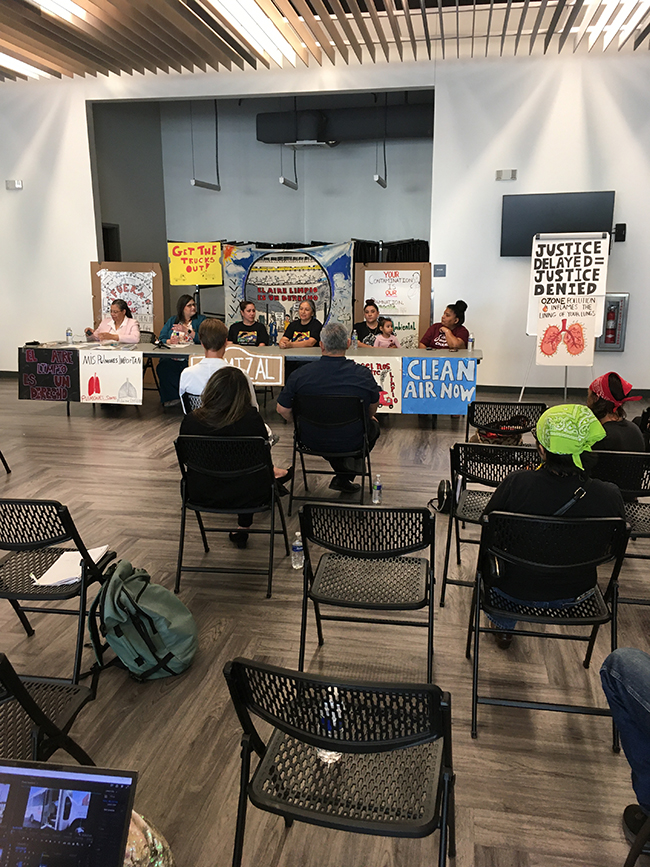

Once the toxic tour concluded, participants reconvened at the Chamizal Community Center for a press conference. Dr. Nance, who administers EPA’s vast Region 6, credited El Paso Congresswoman Veronica Escobar for not only assisting in getting the successful air quality grant awarded, but in helping secure water infrastructure for the Village of Vinton on the northwestern end of El Paso County as well as 25 electric school buses for the Socorro Independent School District in El Paso’s Lower Valley.

According to Nance, funding for the projects in El Paso and elsewhere derives from the “billions” of dollars budgeted for environmental purposes in the American Rescue Plan, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act. “Today, we see these investments taking root in El Paso,” the EPA regional administrator said.

Nance and EPA personnel also distributed information on how local communities defined as underserved and overburdened with pollution can tap into the big pot of federal money, especially highlighting the assistance facilitated by EPA Region 6 to aid potential applicants in navigating complicated paperwork and red tape via two Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers, one situated in New Orleans and the other in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Interested agencies and non-profits can contact the New Mexico center by writing to:. scerc@nmsu.edu

Nance later told this reporter that the Chamizal community registered “extreme” on the agency’s environmental justice screening maps that gauge community exposures.

“I’m very concerned. I think that the community, the group La Mujer Obrera, has identified many of the sources of emissions that might be creating the pollution problem,” Nance said. “Much more needs to be done in terms of monitoring, so we’re glad to be helping them by providing the grant for community based air monitoring. We also have state and federal monitoring going on, and I think the site is worthy of further study.”

For LMO Executive Director Lorena Andrade, the air monitoring grant is a milestone in a long fight to transform an impoverished community where many families struggle to keep food on their tables and roofs over their heads.

Citing the 2020 Census in a summary profile, for instance, LMO reported that two Chamizal neighborhoods registered median incomes below $18,000 per year, while six out of ten households were living below the poverty line. Nearly 60 percent of households with children under 18 were headed by women. Immigrants comprise a large percentage of the population, with 92.8 percent of the residents speaking Spanish.

“Our community has been dumped on, discriminated against, and disregarded for decades,” writes LMO. “Our environmental justice organizing is rooted with those on the ground, the families overburdened by pollution and environmental racism first-hand….”

Once known as the “Garment District” because of the proliferation of garment manufacturers, the Chamizal has undergone immense changes since the day when El Paso was dubbed “The Jean Capitol of the World,” a status which evaporated decades ago with the advent of off-shoring and trade pacts like the North American Free Trade Agreement that led to massive layoffs.

“After the North American Free Trade Agreement there were no more garment factories. They wanted to push us out of the neighborhood and they continue to try to do that,” Andrade said.

“So we decided that this wasn’t the Garment District, (and) that we wanted to call it the Chamizal neighborhood. We started to say we’re not moving, right? We belong in the community,” Andrade reflected. “

We choose to stay here and will not be pushed out, but we are going to get rid of all of these different sources of pollution that exist. We’re no longer going to be dumping grounds. We don’t want to be exploited as women, and we’re not going to allow the earth to be exploited either.”

In the contemporary community and environmental justice movements of the Chamizal, women play the leading role. Still, Hilda Villegas spoke of a bittersweet path to steps ahead like the air monitoring grant.

“It’s kind of really unjust that the burden of (pollution) proof, the burden of accountability is on a community that really struggles on a daily basis just to get the basic needs for themselves and for the women, for us, the children,” Villegas said. “It’s very critical this point with the funding, but I think the government entities need to do more to protect the community.”

Meantime, Familias Unidas de Chamizal and LMO continue urging interested persons to send comments to the U.S. General Services Administration before midnight November 4 in support of removing the diesel-emitting commercial truck traffic from the Bridge of Americas.

Again, the deadline for public comment is tomorrow, November 4. Comments should be emailed to:

Your comment must include “BOTA LPOE Draft EIS” in the subject line.

Thanks Kent, for this important story about a community that is beloved by our Rural Coalition. This support for the years of work of La Mujer Obrera to protect the Chamizal communities. We stand in full support of your work!

Thank you, Kent, for covering important topics that regular media does not show. Issues that impact both sides of the board and private media use to hide from the public.

RSR

Air quality monitors to build a case for…? Did they clear this with Paul, Woody and Ted?

“It’s kind of really unjust that the burden of (pollution) proof, the burden of accountability is on a community”… Yes, you have been abandoned by your city government for 100 years. You and the other legacy neighborhoods are invisible to the city. But it looks like you are taking matters into your own hands which is good. Maybe something will change?