The Way Things Weren’t

Kingston, New Mexico isn’t a ghost town. But it’s also not the place of which it was said that on nights when the miners had been paid you couldn’t walk ninety feet in 30 minutes for the crowd, a place with 22 saloons, 14 grocery stores, three hotels, three concurrently-operating newspapers, an opera house, and a school, a place where the bank once held $7,000,000 in silver and the population topped 7,000. Nope, it’s not that place now. And it never was. There may be few Old West mining boom towns that have had their history so exagerrated. Kingston has even been considered to have once been the biggest town in territorial New Mexico.

Now, everyone agrees that in the early 1880’s precious metal, particularly silver, was found in the area. Ralph Looney’s Haunted Highways recounts the story that Kingston’s establishment can be traced to a drunkard, Jack Sheddon, who became such a nuisance in Lake Valley that the sheriff put him on a burro with food and whiskey and sent him north. En route to Chloride, he made a stop near what would become Kingston, had a good long drink, and passed out on a rock. When he came to, he noticed that his stony pillow had flecks of metal in it. This was bornite, a silver ore, and he quickly established the Solitaire Mine. Soon prospectors were descending from every direction. It’s a great tale, but not really true. Prospecting was underway before Sheddon even arrived (he at least did exist) as a few miners had already moved the 10 or so miles west from Hillsboro, which had been established in 1877.

(The above photo shows a house that was also once a store on Kingston’s eastern edge. The sign in the window says, “Dr Dans Medicine Show 1/22/11”. Near the bottom of this post is a shot of the microwave tree around the side. Interesting, eh?)

In the fall of 1882, James Porter Parker, General G.A. Custer’s former roommate at West Point, platted Kingston, which took its name from a local mine, the Iron King. Soon it was reported by the Tombstone Epitaph in Arizona that there were 45 men working area mines. By 1885, a year after Kingston’s oft-reported peak population of 7,000, Territorial Census figures show 329 residents in Kingston and the adjacent Danville Camp combined, even with Spanish and Chinese included in the tally.

It may well have been a rowdy place though. In an 1886 edition of the St. John’s Herald out of east-central Arizona (at the time Kingston didn’t have one newspaper) a citizen expressed upset at their town’s lack of a school, church, or, indeed, any public institution. Reverend S.W. Thornton even referred to Kingston as “the typical mining town in all its wickedness.” In 1888, construction of a stone church began which would serve Kingston’s now-1,000 residents. Sometimes claimed to have been spontaneously financed by prostitutes, gamblers, and dancehall girls, it’s more likely that Rev. N.W. Chase solicited the funds.

In 1890, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, Kingston’s population reached 1,449, a count it probably never surpassed by much. The 1893 economic panic sent silver prices crashing and the number of Kingston’s occupants plummeting quickly back into the low hundreds at best. By the time it was really all over in the early 1900’s almost $7,000,000 in precious metal had been mined in the vicinity, not an inconsiderable sum. But it took over 20 years; that amount was never in the Percha Bank at one time.

Even the usually no-nonsense Philip Varney slips up when it comes to Kingston, mentioning in New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns that Chief Victorio’s band of Apaches once descended on the town, but because the miners were assembling a hunting party and thus had their firearms at hand they were able to quickly drive the attackers out. It’s said Victorio decided to leave Kingston alone after that and the happy populace named their new three-story hotel The Victorio in his honor. The problem is that Victorio died in 1880, two years before Kingston was established. It’s not entirely Varney’s fault; there are many stories about Victorio and his band’s depredations in and around Kingston. And Varney didn’t have Wikipedia in the 1970’s.

You may also hear of the ironically-named Virtue St., on which was an infamous Kingston brothel. While you will find a very short side street named Virtue today, it was created after Kingston’s initial abandonment. But don’t fret! The world has not gone entirely topsy-turvy; there certainly was a brothel in early Kingston.

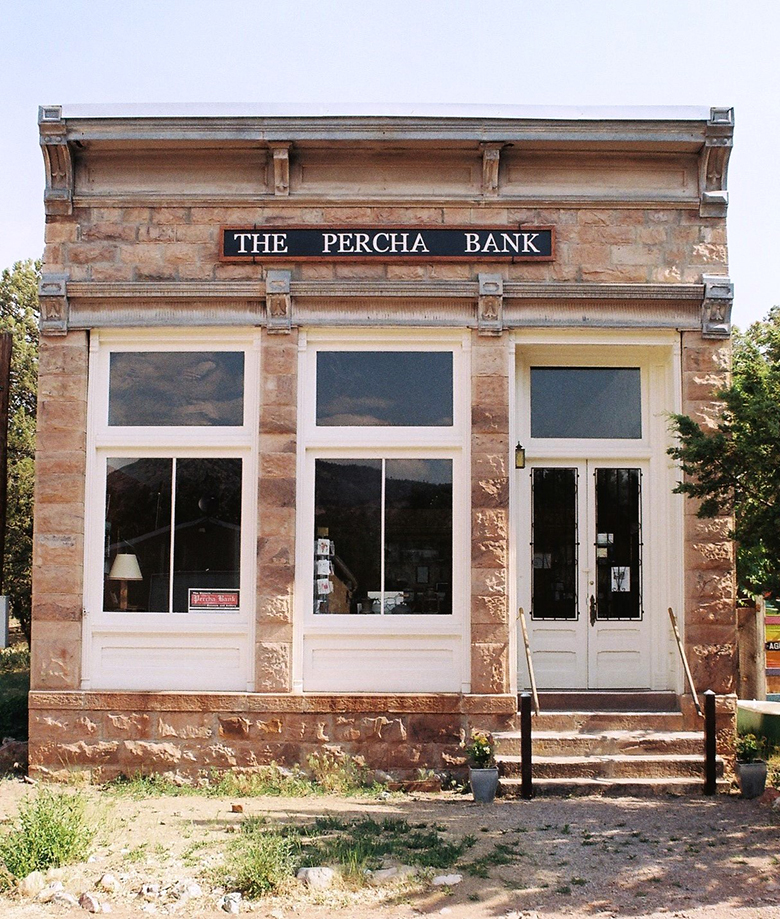

Walking the two short thoroughfares, many have wondered how a town could’ve risen and fallen so precipitously. Since it didn’t, it’s not as surprising that only one historic building exists wholly intact: the Percha Bank. The old Assay Office, remodeled as a private home, and a vastly reconfigured hotel—The Victorio—also persist. Floods and fires have certainly done their damage, but there was never as much to disappear as is usually imagined.

Much of the confusion over Kingston is attributable to James A. McKenna’s classic Black Range Tales, which, it should be noted, contains the word tales in the title and not facts. Some of McKenna’s yarns, which most ghost town sources at least reference, take place in a Kingston of 7,000 rabble rousers, “the metropolis of the Southwest” which, while possibly true to the spirit of the day, never quite existed. The same year that Black Range Tales was published, 1936, Madame Sadie Orchard told an interviewer of a peak population of 5,000. Few having actually been there, such wild overestimates made their way into subsequent Kingston literature. In the end, maybe the Kingston of myth is just one of those places in the Wild West of our collective imagination that people wanted to exist so badly that it was finally wished into being. It’s not the worst thing to have happened to history, I suppose.

Craig Springer, Black Range historian, founding member of the Hillboro Historical Society, and co-author of Around Hillsboro, does the best (and, to date, just about only) full-blown analysis of Kingston’s popular history, at Desert Exposure, turning up many inaccuracies and doing an excellent job of tracking down primary sources of more reliability. I reference his work throughout this post and thank him for his input.

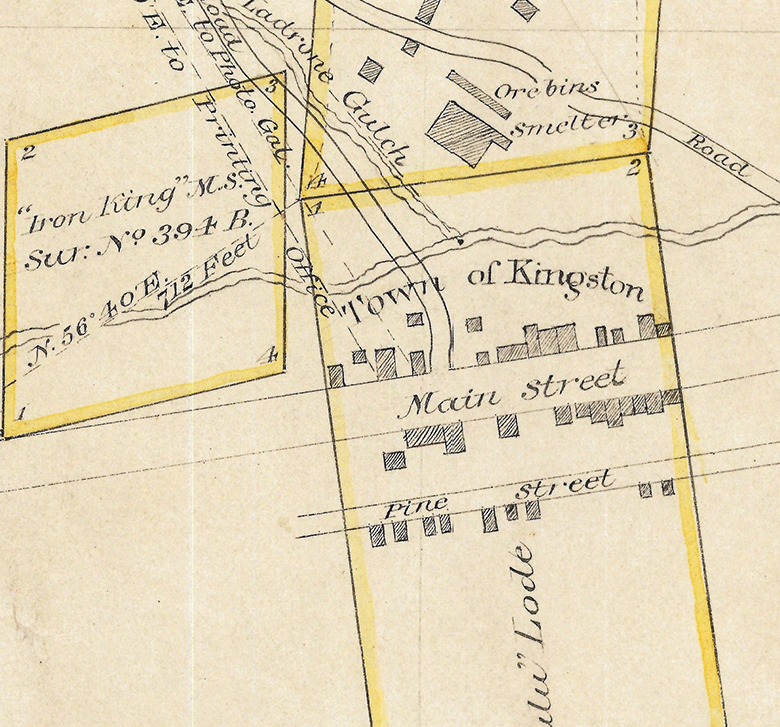

Below is the layout of Kingston circa 1887, which shows that three years after the town’s supposed peak the place was still not real big. The plat is from the General Land Office of the BLM, which has all kinds of good stuff.

Most accounts of Kingston mention Victorio’s harassment, but a quick check of Wikipedia will confirm that he died on October 14, 1880. You might also have heard that Billy the Kid visited Kingston, but as he was shot by Sheriff Pat Garrett on July 14, 1881 in Fort Sumner it would’ve had to have been a very different sort of ghost town then indeed. Finally, if you’re in Kingston don’t forget to check out the real and factual Percha Bank, now a museum! Call before you visit as hours are limited.

John Mulhouse moved to Albuquerque in 2009 after spending the previous decade in Minnesota, Georgia, Tennessee, and California. He loves the desert, realizes it doesn’t care too much about him, and thinks that’s all as it should be. More of his documentation of the lost, abandoned, beaten, and beautiful can be found at the City of Dust blog and the City of Dust Facebook page.

History is important so when I read this self proclaimed expert info., I realize anyone who writes now is a subject mater expert! He is truly plain FOS! Don’t be fulled by his rhetoric look it up!

I guess one could look it up in any of the many sources referenced in this article. Is that what you had in mind?

My great grandfather Charles C. Crews owned property on Bullion Avenue in Kingston. I still pay the Sierra County Property taxes on it. He died in 1874. anyone have any family history from Kingston i would be interested in it. I can be reached at alamoapartments@hotmail.com. Charles E. Mauldi III

I found newspaper articles featuring Charles Crews and relatives(?) on:

Chroniclingamerica.com

Dates:

8-12-1898

1-10-1896

10-25-1918

10-22 -1911

1-11-1908

I’ve stayed a few times at the Black Range Lodge in Kingston where there is good company and food to be found. If only the walls could speak… On one trip, I stopped at that cowboy wine bar in Hillsboro where a woman came in with a sever laceration on her arm. She had been walking her dog when it was attacked by a herd of javelinas and her arm was ripped by a javelina tusk as she tried to pull her dog away from them. I ran out to my car for a first aid kit and we patched her up to stop the bleeding.

Now how many places do you know where you have an adventure like that just a 125 miles from home?