Almost Gone

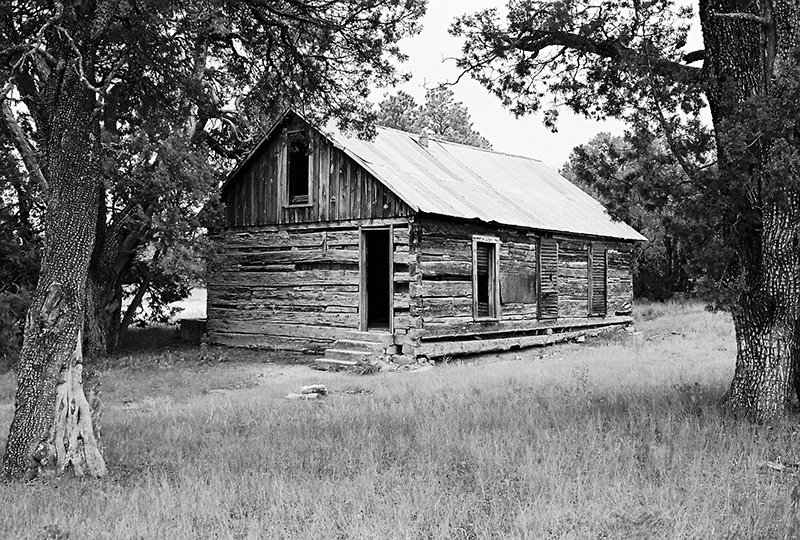

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That’s it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land. I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500s.

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in a previous post recalled going to dances in the schoolhouse. He was also at Normandy and told us some harrowing tales of storming the beach. I may say more about him when I finally do a post on White Oaks.

During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the “Hunt Casita,” after a family that lived there in the late 1970’s. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from Philip Varney of the post office looking quite a bit better than it does now, circa maybe 1980.

I got some information for this post from Legends of America. The story of Jicarilla’s last miner (and a good chronology of area mining) can be found at this link. A relative of the Hunt’s (and friend of Jerry Fennell) provided a little extra detail. Of course, I grabbed a bit of background and general inspiration from Philip Varney.

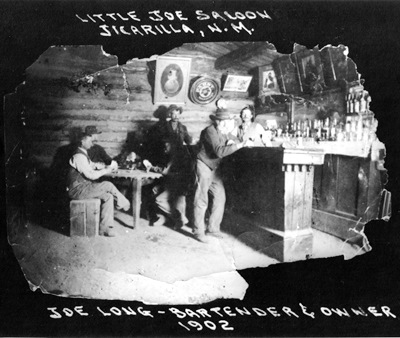

EXTRA: I received a photo circa 1902 of the Little Joe Saloon, which is almost surely the same saloon I refer to above as opening in 1900. It is a wonderful shot submitted by the great-grandson and namesake of the saloon’s original owner, Joe Long, who lived with his wife Viola in Jicarilla in the early 1900’s. Another relative left a comment below about Mr. Long which says that Joe “gave up” the saloon for cattle ranching when his daughter was born in 1908. Apparently Joe and Viola then went on to have 11 more children.

Many thanks to Mr. Long for passing along a fantastic piece of family history which just happens to also be ghost town history.

City of Dust contributor John Mulhouse’s book, “Abandoned New Mexico: Ghost Towns, Endangered Architecture, and Hidden History” will be published on August 29, 2020 by Fonthill Media. Pre-orders are available at Barnes and Noble and Amazon.com.