Bucket of Blood Street, USA

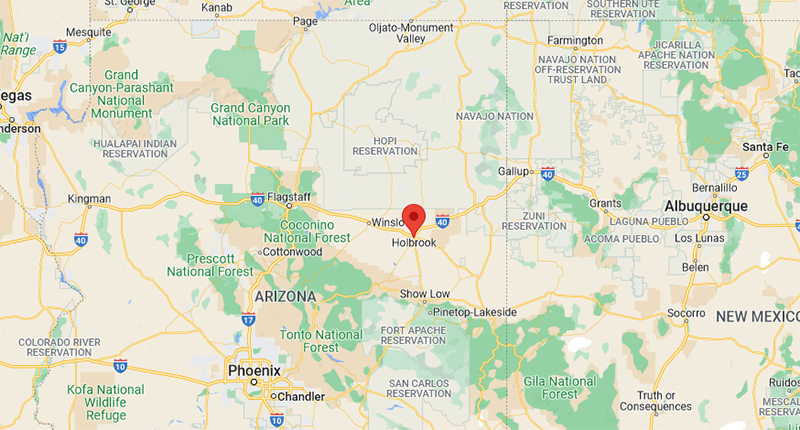

The sun was slowly setting over the Petrified Forest, giant slabs of ancient wood and mountains of white bentonite alternately catching fire and fading into shadow. Driving north on Highway 77, the miles ticked past in streams of rusty barbed wire and broken cars. Millions of glass shards, jagged jewels marking decades of speeding drunks tossing liquid dreams out car windows, glittered from the shoulder of the road and twinkled in the dry yellow grass. Just south of a set of railroad tracks the highway became Navajo Blvd. before intersecting Bucket of Blood St. We stopped the car in the shadow of several tall green dinosaurs. Across the street in one direction was an abandoned tack shop built in the 1920’s. In another direction stood a boarded up wreck of a building made entirely of polished petrified wood. Holbrook (or T’iisyaakin in Navajo), Arizona was suddenly looking like a damned interesting place to spend the night.

In 1881 (or possibly 1882, there appears to be some dispute), Holbrook, named after the first chief engineer of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, was born and immediately became a place to practice the holy trinity of Wild West pursuits: gambling, prostitution and gun fighting. It soon became known as a town “too tough for women or churches.” There was virtually no law in Holbrook and the violence ranged from Apache and Navajo raids on settlers to the Pleasant Valley War, which pitted a family of sheep ranchers against a family of cattle ranchers and lasted ten years, leaving a trail of bodies in its wake.

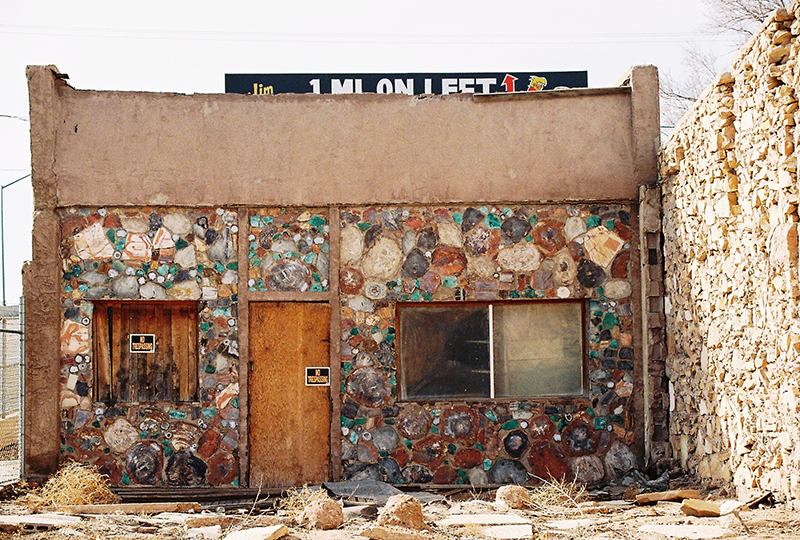

In 1886, the population of Holbrook was about 250 and 26 people died violent deaths, making a citizen’s likelihood of being murdered that year something over 1 in 10. Some of the outlaw cowboys in Holbrook were members of the Aztec Cattle Company and worked for the Hashknife Outfit. These cowboys were involved in the Pleasant Valley War, stole cattle, and shot their guns quite a bit. They were known as the “thievinist, fightinist bunch of cowboys in the west.” The main saloon in Holbrook was, of course, the site of much violence, and had the bucolic name Perkins’ Cottage Saloon. There are two stories as to why the saloon changed its name that year. The first has some of the boys of the Hashknife Outfit accused of stealing cattle while having a drink. A brutal shoot-out is said to have ensued, leaving numerous patrons dead. The second story, told by Albert F. Potter, captain of the Hashknife’s round-up, depicts two Mexican cowboys being shot during a card game by a gambler and a Hashknife Outfit cowboy. The gambler and cowboy quickly rode away on “borrowed” horses. Whichever story is true, it was written that after the incident “buckets of blood” covered the floor of the saloon. Thus the owners decided to change the name of their establishment to better match its disposition. This photo is clearly not of the Bucket of Blood, but it is on the same street.

Over 120 years after its construction, the Bucket of Blood Saloon still stands. You would think that its longevity would ensure that most residents of Holbrook would know its location. Clearly, it’s got to be somewhere on Bucket of Blood St. Yet some locals directed us to the wrong place, telling us that this building made of petrified wood was once the Bucket of Blood Saloon. While a fascinating building in its own right, and probably also a saloon at one time, this was never the Bucket of Blood. The Bucket of Blood is not far away though and I found it somewhat by accident. Not realizing I’d been standing in front of the place until later, the photo below mostly depicts the Bucket of Blood’s neighbor. The Bucket of Blood itself is just to the left, the far-right bit of its lintel just creeping into the frame. I hope to return soon and explore further, now that I’d know what infamy I was looking at.

The year after the shoot-out at the Bucket of Blood Saloon, on September 4, 1887, Commodore Perry Owens, the sheriff of Holbrook, dubbed “Saint George with a six-shooter,” made it known that law and order had finally come to the territory. While serving a warrant on notorious rustler Andy Cooper at the home of the Blevins Gang, the outlaw tried to close the door on the sheriff. Owens fired through the door with his shotgun, hitting Cooper in the stomach. John Blevins returned fire but shot Cooper’s horse instead and was himself shot in the arm. Another man, Mose Roberts, jumped out a window and was killed by Owens. Finally, Samuel Houston Blevins, Cooper’s 15-year-old brother, came out the door and ran at the sheriff pointing his dying brother’s pistol. Owens shot and the boy died in his mother’s arms. In less than a minute the gunfight was over and the back of Holbrook’s cattle rustlers had been broken. Owens, now a legend, remained sheriff until 1896, nearly another ten years. The Blevins House still stands.

In 1895, Navajo County was created by the territorial legislature and Holbrook was designated the county seat. The county courthouse was built in 1898 and used as such for 78 years. There were many trials but only one man, George Smiley, convicted of murder, was ever executed. His hanging became notorious for an unusual reason. In the late 1800’s, Arizona law required that every sheriff in Arizona, as well as certain public officials, received an invitation to each execution scheduled to occur in the state. Commodore Perry Owens’ successor, Sheriff Frank Wattron, could find no official format or template for such an invitation so he designed his own, complete with flowery language and a gilt-border. It read:

“You are hereby cordially invited to attend the hanging of one George Smiley, murderer. His soul will be swung into eternity on December 8, 1899, at 3 o’clock p.m., sharp.

Latest improved methods in the art of scientific strangulation will be employed and everything possible will be done to make the surroundings cheerful and the execution a success.

F.J. Wattron, Sheriff of Navajo County.”

It sounded like quite an enjoyable afternoon, but President McKinley believed an execution demanded a certain amount of gravity and, when word of the invitation reached him, he contacted the Governor of Arizona to issue a stay of execution for 30 days and gave Sheriff Wattron a personal reprimand.

So, the sheriff set about writing another invitation. This time it read:

“Revised Statutes of Arizona, Penal Code, Title X, Section 1849, Page 807, makes it obligatory on sheriff to issue invitations to executions, form (unfortunately) not prescribed.

Holbrook, Arizona

Jan. 7, 1900.

With feelings of profound sorrow and regret, I hereby invite you to attend and witness the private, decent and humane execution of a human being; name, George Smiley, crime, murder.

The said George Smiley will be executed on Jan. 8, 1900, at 2 o’clock p.m.

You are expected to deport yourself in a respectful manner, and any ‘flippant’ or ‘unseemly’ language or conduct on your part will not be allowed. Conduct, on anyone’s part, bordering on ribaldry and tending to mar the solemnity of the occasion will not be tolerated.

F.J. Wattron, Sheriff of Navajo County.

I would suggest that a committee, consisting of Governor Murphy, Editors Dunbar, Randolph and Hull, wait on our next legislature and have a form of invitation to executions embodied in our laws.”

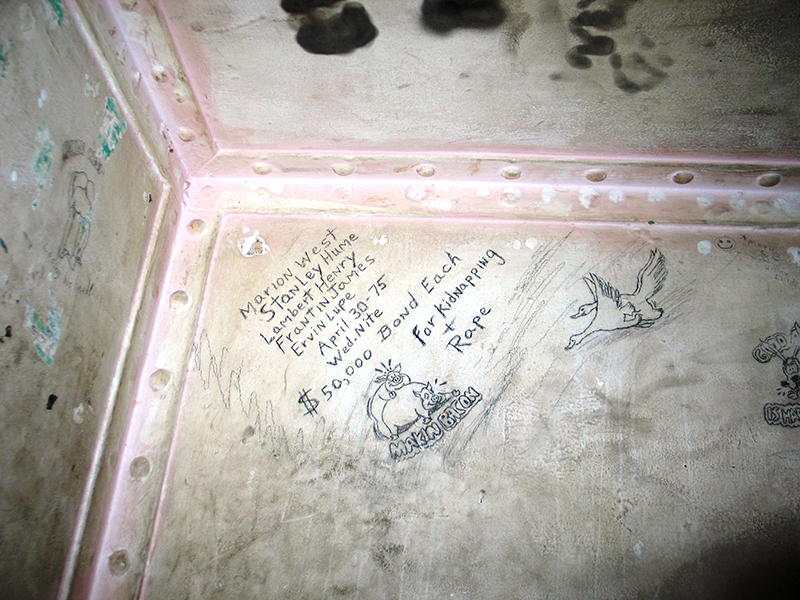

To ensure the thinly-veiled sarcasm of this second invitation did not result in another letter from President McKinley, Sheriff Wattron sent the invitation out one day before the execution date. George Smiley swung before news of the second invitation ever reached Washington, D.C. and he now haunts the courthouse, perhaps waiting for another message from McKinley, one that will never come. The photo above and the one below are both from the jail in the old Navajo County Courthouse. The night of Wednesday, April 30, 1975 was not a good one in Holbrook.

After reliving the brutality of American history, why not stay in a Wigwam for the night? Wigwam Motel #6 (there were once seven Wigwam Motels throughout the country; three survive) is on Hopi Dr., in central Holbrook. It was built in 1950 and is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Of course, a wigwam is a domed-structure and the “rooms” at the Wigwam Motel are more properly teepees. But why split hairs? There’s a vintage jalopy parked in front of each teepee and when the sun sets it’s not hard to imagine you’re in the real thing.

One last quick fact about Holbrook: On July 19, 1912, a 400 lbs. meteorite exploded over the town. It’s estimated that more than 16,000 stones fell out of the sky, some weighing almost 15 lbs. I guess danger takes a variety of forms in Holbrook.

There’s not too much on the web about Holbrook, but the sites I found most useful were one on the BUCKET OF BLOOD SALOON and another on the NAVAJO COUNTY COURTHOUSE. I also got some information from the Northeastern Arizona Daytrip Guide.

If you want to visit Holbrook and stay at the Wigwam Motel, their website is HERE.

City of Dust creator John Mulhouse’s new book, “Abandoned New Mexico: Ghost Towns, Endangered Architecture, and Hidden History,” published by Fonthill Media, is now available at: https://cityofdust.bigcartel.com/.