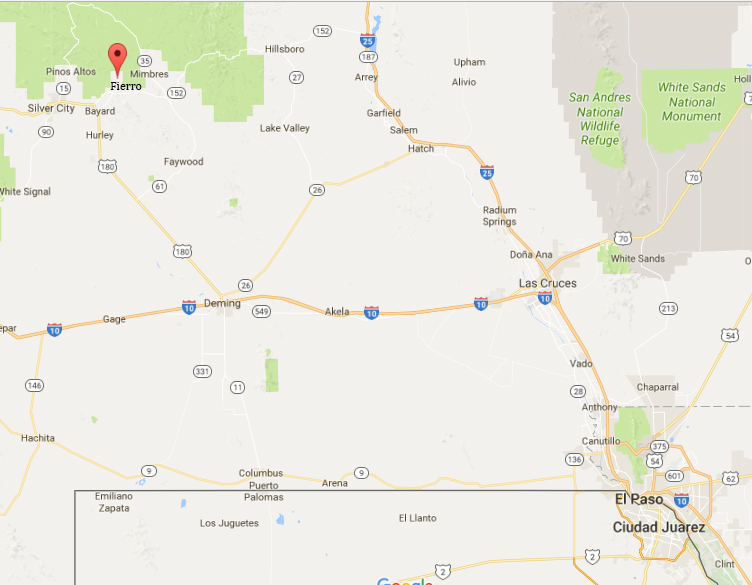

Iron Town

Let’s pay a visit to Fierro, New Mexico, in the southwestern part of the state, a few miles due east of Pinos Altos. For a true ghost town, it’s still got a good number of buildings which, while certainly falling, aren’t completely down and out yet, and it has plenty of lonely charm. All you’re likely to hear while exploring is the occasional sound of wood scraping tin when the breeze picks up and maybe the caw of a crow or two flying overhead.

Fierro is an archaic form of hierro, the Spanish word for “iron,” and iron is the reason the town was born in the first place. The mining history goes back to 1841, when Sofio Henkle (or Hinkle), a German immigrant living in Mexico, went looking for copper deposits. He found both copper and iron on a mountain a few miles north of the big copper mine in Santa Rita and named the mountain and its new mine Hanover, after his former home. The town just a couple miles south of Fierro would also be called Hanover.

Henkle, however, was soon driven out by Apaches and lucky to escape with his life; he’d been warned of an imminent attack by a friendly Apache woman. Henkle returned years later after New Mexico became a U.S. Territory, believing that he’d be alright now that the army was guarding mines. But then the Civil War required most Federal soldiers to head east and Apaches and Confederates started raiding. So Henkle gave up for good and lived the rest of his life in the Mesilla Valley to the south.

As the 19th century wound down, with the threat of Apache raids gone, and the railroad already having arrived at Silver City—about 15 miles southwest—by the early 1880’s, Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) took an interest in the iron ore deposits of Fierro. A post office was established in 1899, about when the railroad reached Fierro itself, and as much as ten carloads of ore started getting shipped out each day to Pueblo, Colorado, where CF&I were based.

(Above is a home I believe was originally owned by the Bacon family and then the Drakes. Its last owners were the Araujo family, who rented it out.)

The population of Fierro was 750 in 1920 and probably never much over 1,000, even during the peak years between WWI and the start of the Great Depression, by which point six million tons of iron had come from Fierro’s mines. Seventy-eight percent of Fierro’s population was of Mexican descent in 1920, and that percentage increased, reaching the high nineties once the mines closed.

The mines shut down in 1931, although the large Continental Mine ran intermittently and, tragically, in 1947 four miners were killed near it in a “short fuse” accident. While the Cobre Mining Company resumed operations, now with an emphasis on copper, and some residents stayed at least into the 1990’s, Fierro never recovered from the economic blows of the early 1930’s, when people began to leave quickly, many for gold mines in California.

The Gilchrist and Dawson Store, Mrs. Rel’s Rooming House, Filiberto’s Variety Store, McCoy’s Store and post office, John Oglesby’s silent movie house, Sheriff Mac Minter’s pool room; these places were frequented by the miners and their families. Now they’re all gone. Some of them burned in a fire in 1923 when a miner from Mogollon went to sleep at Mrs. Rel’s following a fandango next door and kicked over a kerosene lamp in his room. Without a fire department, and with some buildings even having sidewalks made of wood, much of Fierro’s early commercial district burned fast.

(Below is the Phoenix Mercantile (aka La Tienda del Finicas), which even sold fine furniture. Later it became Araujo’s Grocery and housed the post office. Sitting on the steps waiting for the mail was a common pastime in Fierro.)

Another building of interest is the little jail by the railroad tracks, near the arroyo that runs through the town (pictured below). In Black Range Tales, James McKenna recalled visiting Fierro in the 1880’s and noted that mining towns punished wrongdoers by tying them to a thick log which had been sunk in the earth with eight feet remaining above ground. Normally prisoners would be released once they’d sobered up and/or calmed down. That could easily take all night. Fierro reportedly did away with its log in the early years, even though the sturdy concrete jail probably never held any true desperadoes.

Fierro was known for its love of baseball, with three different fields being used during the town’s history. In the late 1930’s, the team went by the seemingly unusual name “Peru Miners.” Basketball was also popular, with games being played on the school’s dirt court until it was paved in the 1930’s. Fierro even had a Boy Scout troop as late as the 1940’s.

One interesting tradition in Fierro was El dia de las Travesuras, The Day of Pranks, which was a replacement for Halloween. On that night there was no trick-or-treating in Fierro. Instead, kids played pranks, the most common of which was to tip over outhouses. One man spent a night in his outhouse with a shotgun to prevent any hi-jinks, only to have his bathroom toppled anyway when he went back to his house at 2AM for a quick cup of coffee. This never happened to the managers of CF&I as they had indoor plumbing and even electricity. Later, it’s said that a popular prank was swapping around railroad and highway signs, which might cause problems regardless of income bracket.

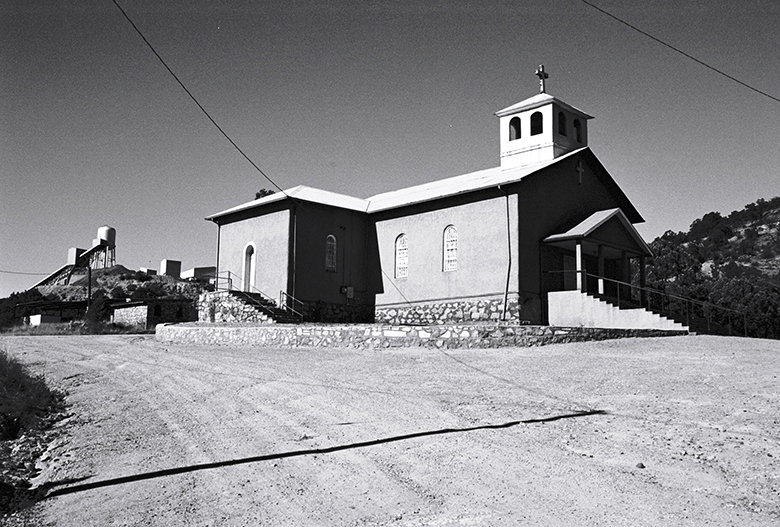

While Fierro is a ghost town now, two places that are very much alive are St. Anthony’s Mission Catholic Church (above), built in 1916 and later enlarged, and, ironically enough, the cemetery, which covers four acres and is lovingly maintained these days. Aside from regular services, a celebration and mass is still held each year on June 13th, the Feast of St. Anthony, and many of those for whom Fierro remains important meet to reminisce and once again walk the quiet streets of the old place.

Some information for this post came from “New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns,” “Ghost Towns Alive,” and “The Place Names of New Mexico,” but the best place to learn about Fierro is “Remembering Fierro (Again) (Revised Edition)” by Frank Ramirez [if you can find it]. It’s not very often that an out-of-the-way ghost town has an entire book dedicated to it, but I’m certainly pleased on the rare occasions when it happens. Mr. Ramirez passed away in 2011 and this post is dedicated to him.

John Mulhouse moved to Albuquerque in 2009 after spending the previous decade in Minnesota, Georgia, Tennessee, and California. He loves the desert, realizes it doesn’t care too much about him, and thinks that’s all as it should be. More of his documentation of the lost, abandoned, beaten, and beautiful can be found at the City of Dust blog and the City of Dust Facebook page.

Ana Egge, a folk singer who lived in Silver City for a while, wrote a song about the town called “Fierro” which got some air play back in the day. I haven’t heard it in some time, but I seem to remember something about striking miners. The song is on her 1999 release “Mile Marker.”

She played at Wildhare’s.

Here’s Fierro, from BandCamp.com:

https://anaegge.bandcamp.com/track/fierro-2

Almost 70 years ago, my family lived at the “Thompson Place” just north of downtown Fiero. I went to grade school at the school at the top of the hill. Fiero was a great little town where everyone helped each other. Many times we would drive into Bayard or Silver City to buy groceries and other supplies. We would have two or three residents of Fiero along with us, or we had a list of things others wanted us to pick up for them. When we moved out of the Thompson Place the building quickly dissolved down to a barren foundation, and was quickly resurrected in other homes and outbuildings in Fiero proper. The population didn’t give up on the town. Residents either died in their homes or went to live with relatives but grew too old to return. Fiero was born by removing things from the earth and is now slowly returning to that same earth.