Days Too Late

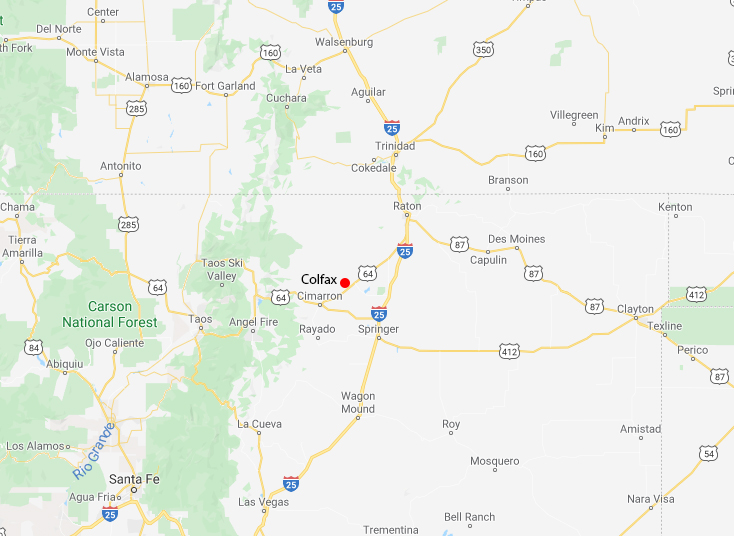

Originally known as Vermejo Junction, Colfax was established in 1869 and took its name from Schuyler Colfax, Jr., the 17th Vice President of the United States. Colfax served under President Ulysses S. Grant. It’s anybody’s guess as to why the town was named after Schuyler, but what is known is that, unlike other mid-nineteenth century towns in New Mexico, Colfax was promoted not for its mineral resources, but as an ideal place for agriculture. It was largely the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific Railroad, which ran nearby, doing the promoting. Two thousand 25′ x 140′ lots were laid out and sold for $140 a pop, with discounts for anyone buying more than one. Given the importance of the railroad in those days, there was every reason to expect that people would come to Colfax. But, in the end, not many did. Some would-be residents were even cheated by crooks who did not actually own the plots they sold.

By 1908 Colfax had a post office but it closed in 1921. A school, hotel, mercantile store, and even a gas station survived into the Great Depression. The school, which also functioned as a church, remained open until 1939. But most people coming into the area simply opted to go up the road a couple miles to Dawson to work in the mines or they set up shop in Cimarron. Thus, Colfax seems to have never really gotten off the ground.

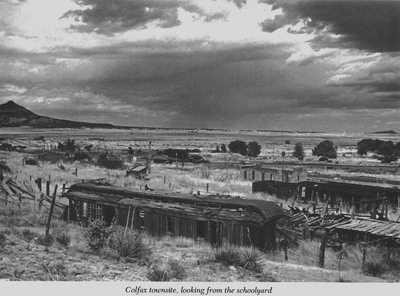

The two-story Colfax Hotel (originally known as the Dickman Hotel) was the major structure in the town, but it eventually went out-of-business and has been gone many, many years. Philip Varney’s guide to New Mexico’s ghost towns contains photos of both the old school and a panorama of what remained of the town about 30 years ago. In the panorama a passenger coach railroad car can be seen, along with some other intriguing structures. I really wanted to have a look at the railcar, in particular. There are great photos of it (and Colfax in general) taken in early 2009 at Rocky Mountain Profiles. And an old car shot through with bullet holes? There was every reason to be excited. But, in the end, it turned out there was almost nothing of Colfax left to be seen except for char marks on the ground where something had stood just weeks, if not days, prior to our visit.

So, what happened? Did someone set the old buildings of Colfax on fire? That’s a likely guess. Most of Colfax’s structures were just feet from U.S. 64 and being only 13 miles from Cimarron did leave the place open to mischief. In a way, it’s surprising the wooden buildings lasted as long as they did. I tried to recreate Varney’s panorama and, while he was a bit upslope from me, you can still match up the blackened ground with the structures in his photo. Did the railcar burn? What about the assorted outbuildings? The caption of Varney’s shot says, “Colfax townsite, looking from schoolyard.” I sure didn’t see any school. The stone wall at the top of this post is really the only thing left. If only we’d gotten to Colfax just a few weeks earlier in its quiet 142-year history we might’ve caught its last gasp before it finally sank below the roiling waters of time for good.

Almost no information on Colfax exists that isn’t taken from Philip Varney’s book, although Rocky Mountain Profile’s write-up contained a few tidbits, in addition to the excellent photos. I scanned Varney’s panorama and posted it here to depict Colfax’s almost complete disappearance. Thanks, Mr. Varney, wherever you may be.

City of Dust contributor John Mulhouse’s book, “Abandoned New Mexico: Ghost Towns, Endangered Architecture, and Hidden History” will be published on August 29, 2020 by Fonthill Media. Pre-orders are available at Barnes and Noble and Amazon.com.