Here’s a story from the New York Times headlined “The Next Affordable City Is Already Too Expensive.” The names are different, but the story sounds familiar.

Maybe it was the date night when he and his wife spent two hours driving 19 miles to dinner, or the homeless encampment down the street, or the fact that homes were so expensive that his children could never afford to live near him.

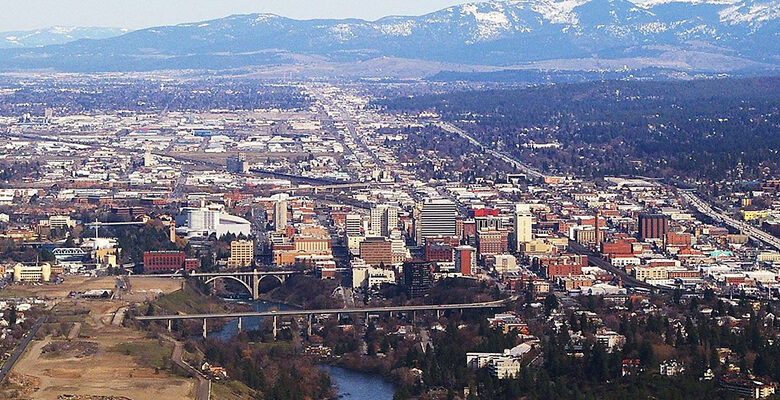

Whatever the reasons, and there were many, Steve MacDonald decided he was done with Los Angeles. He wanted a city that was smaller and cheaper, big enough that he could find a decent restaurant but not so much that its problems felt unsolvable and every little task like an odyssey. After the pandemic hit and he and his wife went through a grand reprioritizing, they centered on Spokane, where their son went to college. They had always liked visiting and decided it would be a nice place to move.

Eastern Washington was of course much colder. Until this winter, Mr. MacDonald, a native Southern Californian, had never shoveled snow. But their new house is twice as big as their Los Angeles home, cost less than half as much and is a five-minute commute from City Hall, where Mr. MacDonald works as Spokane’s director of community and economic development.

He arrives each day to tackle a familiar conundrum: how to prevent Spokane from developing the same kinds of problems that people like him are moving there to escape.

. . .

Just a few years ago, a Spokane household that made the median income could afford about two-thirds of the homes on the market, according to Zillow. Now home prices are up 60 percent over the past two years, pricing out broad swaths of the populace and fomenting an escalating housing crisis marked by resentment, zoning fights and tents.

Remember this story from this week’s El Paso Inc.?

It’s getting more difficult to buy a home in El Paso, especially for the middle class – a nationwide trend that has hit homebuyers in the borderland especially hard.

Housing affordability has eroded since 2019 and through the pandemic, as home prices have soared and inventory has plummeted, according to a new report by the National Association of Realtors that looked at housing affordability by income bracket.

In December 2019, the share of homes in El Paso considered affordable for households earning between $50,000 and $75,000 was 55%. Two years later, in December 2021, only 32% were considered affordable, according to the report.

According to the City of El Paso, the median household income in El Paso is $42,075. That information is old, but they’ve been too busy not paving our streets to keep their Economic Development website up to date. The Census Bureau puts El Paso’s median household income at $47,568 in 2019.

Back to Spokane:

Being an “it” place was something Spokane’s leaders had long hoped for. The city and its metropolitan region have spent decades trying to convince out-of-town professionals and businesses that it would be a great place to move. Now their wish has been granted, and the city is grappling with the consequences.

Growth is never perfect, and Spokane’s influx has been accompanied by a booming employment market that has increased wages, turned abandoned warehouses into offices and helped the city recover jobs lost during the pandemic. This is normally called progress. But for people who already lived in and around Spokane or the suburbs just across the border in north Idaho, the shift from living in a place that was broadly affordable to broadly not has come on with the suddenness of a car crash. Now many workers are wondering what the point of growth is if it only makes it harder to keep a roof over their head.

. . .

Spokane is the largest city on the road from Seattle to Minneapolis. This fact is frequently cited as the logic behind its economy: It’s between things. The city was incorporated in 1881 and grew into a transportation hub for the surrounding mining and logging industries. It remains a hub, only instead of shipping out timber and silver, businesses revolve around Fairchild Air Force Base and a collection of hospitals and universities that draw from the rural towns that stretch from eastern Washington to northern Idaho and into western Montana.

El Paso isn’t surrounded by a bunch of rural towns. El Paso is a long way from anywhere, except maybe Juarez. Las Cruces has its own hospitals and university. So does Juarez, and most of the residents of Juarez are legally prohibited from entering the United States.

Five years ago, a little over half the homes in the Spokane area sold for less than $200,000, and about 70 percent of its employed population could afford to buy a home, according to a recent report commissioned by the Spokane Association of Realtors. Now fewer than 5 percent of homes — a few dozen a month — sell for less than $200,000, and less than 15 percent of the area’s employed population can afford a home. A recent survey by Redfin, the real estate brokerage, showed that home buyers moving to Spokane in 2021 had a budget 23 percent higher than what locals had.

. . .

The recent Realtors report warned of “significant social implications” if the city doesn’t tackle housing. The issues included young families not being able to buy or taking on excessive debt, small businesses not being able to hire, difficulty keeping young college graduates in town.

I’m thinking El Paso might be in better shape to deal with the problems cause by rapid growth if we hadn’t taken on so much extra debt for the benefit of the developers and real estate speculators.

Of course, responsible forward thinking has never been one of the City’s strong points.

Read the whole story on the New York Times website to fill in the missing pieces.

“how to prevent Spokane from developing the same kinds of problems that people like him are moving there to escape.”

Don’t Californicate it, i.e., people who leave the Golden State because it became unaffordable and insufferably woke only to demand the same kinds of policies (mainly land use and environmental) that make their new home the next California. Affordable housing is at the base of the social ladder to the America Dream and is long gone in many places now; it exists in tension with open spaces and roads. No free lunch.