By Bob Chessey

Gabriel Jara and “El Contrabando de El Paso”

On the night of August 7, 1924, a somber group of 38 men and two adolescent boys were preparing to board an east bound train at El Paso’s Union Depot. Because a large amount of time would pass before this party would reunite with their loved ones, heartfelt farewells were being exchanged by the travelers and their well-wishers. The leader of this group of male travelers was US Deputy Marshal James J. Hill who, accompanied by six guards, was tasked with transporting the 31 federal prisoners to Leavenworth Penitentiary in northeast Kansas; the two boys were destined for the reformatory school at Booneville in Missouri. Of the prisoners, 14 were sentenced on narcotic charges to Leavenworth, as were the pair of juveniles bound for the reformatory; sixteen of the men were convicted of violating the liquor law violations. 1

Deputy Marshal Hill has been captured in local folklore. In 1983 El Paso resident Salvador Ballinas documented his memories and experiences of growing up in the Segundo Barrio (Second Ward) of south El Paso and recalled Deputy Marshal Hill escorting prisoners to the train station, “The federal and state prisoners were sent by train to serve their terms in prison. These prisoners were taken from the El Paso County Jail, in the Court House, on foot and handcuffed, to the Union Depot. This practice continued for many years, and the U.S. Deputy Marshal (or Guard), Mr. Hill, who accompanied the prisoners to the Depot, came to be well known by El Pasoans. While on their way to the Depot, the prisoners could talk to their loved ones and say goodbye. These were sad moments with wives, mothers, and children crying. A Juarez liquor smuggler who served time in prison composed a song called ‘El Contrabando de El Paso’. The song, which mentions Mr. Hill, became very popular and still is sung by many Latin residents in El Paso.” 2

The section of the Spanish language corrido “El Contrabando de El Paso” focusing on Deputy Marshal James J. Hill arrives in Part One of the historic ballad:

“le pregunto a Mr. Hill, que si vamos a Louisiana.

Mr. Hill con su risita, me contesta:—no señor,

pasaremos de Louisiana.

derechito a Leavenworth.”

“I ask Mr. Hill, if we are going to Louisiana.

Mr. Hill, with his little smile, replies: “No sir,

we will go through Louisiana,

and straight to Leavenworth.” 3

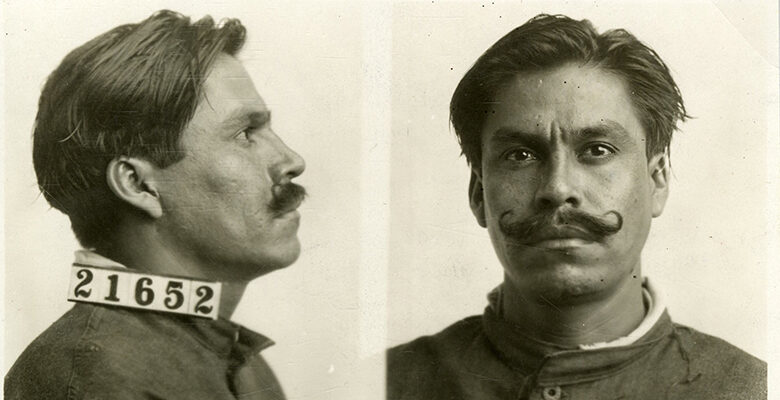

Coincidentally, the person credited with composing “El Contrabando de El Paso’ was a member of the August 7, 1924, Leavenworth bound boarding party—Gabriel Jara, the alleged prisoner of Tom Threepersons on the night of the June 14th gunfight on the American bank of the Rio Grande. In 2004 the Arhoolie recording label released a compact disc (CD) entitled THE ROOTS OF THE NARCOCORRIDO that presents that composition and 25 additional Spanish language smuggling ballads recorded between the years 1927 and 2000; however, the events described in the collection of corridos span the years 1888 to the 1970’s.

The highly influential smuggling ballad CONTRABANDO DE EL PASO (PARTS I & II) was recorded by Luis Hernández and Leonardo Sifuentes for pioneering talent scout and record producer Ralph Peer. The famed producer had arrived in El Paso in mid-April 1928, to locate and record songs in a temporary studio at the Baptist Publishing House, 800 Myrtle Street, for the Victor Talking Machine Company’s Latin music catalogue. On Peer’s first day of sessions in El Paso, April 15, 1928, Hernández and Sifuentes stepped before a microphone and recorded the first of three songs the duet laid down on an acetate disc, Contrabando de El Paso. 4 The smuggling ballad was captured for posterity two and a half years after Jara’s October 23, 1925 release from Leavenworth; 5 and would become the best-known song from the catalogue of Ralph

Peer’s 1928 and 1929 El Paso recording sessions.

Information printed for the track CONTRABANDO DE EL PASO (PARTS I & II) in THE ROOTS OF THE NARCOCORRIDO accompanying booklet notes that the ballad was so well received that between August 1928 and October 1929 four additional duets recorded the corrido five other times. The booklet quotes the late University of California at Los Angeles Professor Guillermo Hernández, whose research for this ballad 6 was based upon an unpublished manuscript in his possession titled “El corrido en la historia cultural mexicana”:

“This corrido is based on the life experience of its author, Gabriel Jara, who spent two years as a prisoner in Leavenworth prison. Accused and sentenced for smuggling alcohol into the United States during the Prohibition Era, Jara was released and deported to Mexico in October 1925. His friend, Leonardo Sifuentes, along with Luis Hernández, made the first recording of ‘El Contrabando de El Paso’”. 7

In the accompanying CD liner notes for the corrido Professor Hernández mentions Jara had been sentenced to two years at Leavenworth Penitentiary. However, the El Paso Herald, which listed the prison sentences of Jara and the other convicted federal prisoners being transported from Union Depot on August 7, reported that Jara was sentenced to 18 months and a $250 fine, 8 the sentence and fine reported in the Herald is confirmed by Jara’s Leavenworth documentation 9 .

In October 2005, Professor Hernández published an article in Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies titled, “En busca del autor de ‘El contrabando de El Paso’” (In search of the author of “El contrabando de El Paso”). The Aztlan article lays out how Hernández undertook two basic stages in his research. The first was to examine the lyrics of the corrido, which are written in the first person, to extract any possible identifying information. This includes the date of the narrator’s departure for Leavenworth, and, while waiting for the train, his scanning the station with the hope of seeing his mother and wife among the sendoff crowd; and his disappointment that neither woman is in attendance to personally tell him goodbye. Because of the convicted smuggler’s expectation for both women to have been present at the train station, the professor concluded that the protagonist, mother, and wife, most likely lived in El Paso, Juarez, or the general region.

The second stage of research tapped into the Leavenworth Penitentiary records housed in the National Archives at Kansas City. Professor Hernández initiated a process of elimination concerning all the members of El Paso’s August 7th Leavenworth boarding party. Of the 33 inmates transported that evening he was able to rule out those that were not married, had mothers living far away, prisoners who were Anglo, and the juveniles who were transported to a detention facility in Missouri. At the conclusion of this screening the list of potential inmates was narrowed down to four possibilities, one of whom was Gabriel Jara.

When Hernández sifted through the final four candidates’ lode of prison documentation, he struck paydirt with Leavenworth’s record of Gabriel Jara’s postal correspondence; Jara had exchanged multiple letters with Leonardo Sifuentes. This realization established a direct connection, before the corrido was recorded, between Jara and a member of the Juarez based duet who first released “Contrabando de El Paso”. There were at least seven letters between the two men while Jara served his prison term in Leavenworth. Of those seven letters, only one, possibly two, of the correspondences were sent by Sifuentes, with Jara having penned the majority.

Unfortunately, all that exists is a document proving that letters between Jara and Sifuentes had been sent and received; the actual letters and their texts are lost to history.

Professor Hernández established that Jara, like the narrator of the corrido, was arrested for smuggling liquor, left El Paso on August 7th on a train bound for Leavenworth, had a wife, though apparently estranged at the time of his incarceration, a mother, with whom he did exchange some letters, and a verifiable link between Jara and the first musicians to enter a recording studio and set, “El contrabando de El Paso,” to disc.

Acknowledging that the evidence he presented was circumstantial, Professor Hernández conceded that he could not conclusively prove that Gabriel Jara was the composer of “El contrabando de El Paso”.

Though Hernández presents evidence that grabs one’s attention, the supporting facts remain circumstantial. For example, Hernández never considers an alternate interpretation of the information he discovered, the possibility that Gabriel Jara had no active role in composing the ballad, but, instead, Jara had shared with Sifunetes, either by letter or in person, what he had observed and had been thinking about his arrest, sentencing, and transport to Leavenworth prison while awaiting his departure from the El Paso train station platform, and those thoughts and feelings then served as the model or template for the corrido. In addition, it has never been established, or even suggested, whether Jara did, or did not, have the ability to write lyrics or poetry, play an instrument and/or carry a tune. The smuggling corrido could just as easily have been written by either Hernández, Sifuentes, or both musicians. Or with the assistance of another musician friend of the musical duo.

The date of the first recording of the ballad is known, but not when it was composed, the song could have been written in Juarez while Gabriel Jara continued serving his prison sentence more than 900 miles away in Leavenworth. Equally feasible is that the song was written and performed for months before Gabriel Jara was released from the penitentiary and deported back to Juarez.

Professor Hernández’s qualified attribution of Jara’s authorship of the smuggling ballad was repeated in a recent book, UNA HISTORIA TEMPRANA DEL CRIMEN ORGANIZADOS EN LOS CORRIDOS DE CIUDAD JUÁREZ, by Juan Carlos Ramírez-Pimienta, that examines corridos dating from the 1920’s through the mid-30’s and share narratives focusing on early organized crime in Ciudad Juárez. Ramírez points out that the prison letters between Sifuentes and Jara documents a connection and probable friendship, is strong circumstantial evidence linking Jara to the originators of the corrido,

but does not establish definitive corroboration that the convicted smuggler was the author of Contrabando de El Paso. 10 In his research, Ramírez has discovered others who stake a claim to having been the composer of the historic corrido, though none of those challengers present a case near as persuasive as Jara’s defense as the historic song’s writer 11 .

If one grants the benefit of doubt and assumes that Gabriel Jara was the sole composer of “El contrabando de El Paso”, or even the lyricist of the corrido, that position reinforces the argument that Jara was not the first and final prisoner of Tom Threepersons on the eventful night of June 14, 1924.

Though the lyrics of the ballad are written in the first-person the narrative does not complain nor protest about being substituted for a different smuggler, nor does the narrator mention a prolonged gun battle between Customs and his comrades that positioned him in the center of gunfire. Nonetheless, the most persuasive evidence that Gabriel Jara was not Tom Threepersons’ escaped smuggler is contained in the lyrics of the first stanza in part II of Contrabando de El Paso. In that section of the corrido the composer expresses resentment directed toward his smuggling “compañeros”, his companions who had abandoned him after his arrest. In that section the ballad warns those who may be contemplating liquor running to be cautious:

“no se crean de los amigos

que son cabezas de puerco.

Que por cumplir la palabra,

amigos en realidad,

cuando uno se halla en la corte,

se olvidan de la amistad.”

“do not trust in your friends,

for they are self-serving hypocrites.

I kept my word,

Like a true friend,

but when one lands in jail,

your friends forget all about friendship.” 12

These lines in the corrido convey the lyricist’s disappointment that his confederates forgot about him after he was taken into custody. However, if Jara had been the handcuffed prisoner of Tom Threepersons, it would have been evident to him that his fellow smugglers had waged an hour-long armed attempt to secure his release before he could be taken to jail, and that one of the smugglers had been killed by Threepersons and had sacrificed his life during the rescue attempt. For that effort alone, if Jara was the prisoner, and the song’s author, even though his compatriots may not have visited him in jail or during his departure for Leavenworth, it does not seem he would have been as bitter as the lyrics come across.

In federal court Gabriel Jara admitted to having smuggled two sacks of liquor into El Paso from Mexico. That one statement is the sum total of his known personal testimony regarding his arrest and trial.

The limited lyrical evidence that would directly link Jara to the corrido is the date of his departure to Leavenworth from Union Depot, that he was married, and his mother was alive. The shared departure date with the corrido could simply be a tip of the hat by Sifuentes and Hernandez to Jara but does not seal the proof that Sifuentes’ friend was the composer or lyricist of Contrabando de El Paso.

Contrabando de El Paso is a cautionary ballad about the pitfalls of liquor running. And if the benefit of doubt is bestowed to Jara as the composer, and extended further to include he was also Tom Threepersons’ elusive prisoner, why did he not expand on the cautionary elements of his predicament in his corrido? The pioneering ballad could have warned of life-threatening gun battles with law enforcement, companions getting killed in the gunfire, and escaping from his captor led only to his being rearrested. Each of those particulars would have carried additional weight and potency.

Returning to Salvador Ballinas’ Segundo Barrio reminiscence, 55 years after the recording of the song, that “A Juarez liquor smuggler who served time in prison composed a song called ‘El Contrabando de El Paso’”, was Mr. Ballinas declaration because he had credible information that a convicted rum runner had actually written the pensive ballad; or, simply an assumption based on the corrido’s tale unfolding in the first person? It is also quite plausible, over the ensuing decades, that other convicted liquor smugglers from the area had claimed credit for having written the corrido and Ballinas was thinking of one of those individuals. In addition, Mr. Balinas does not name Gabriel Jara as the prisoner in question. As a result, Mr. Ballinas casual mention that the ballad was written by, “A Juarez liquor smuggler who served time in prison,” becomes one more evidentiary tease.

As mentioned previously, El Contrabando de El Paso was recorded a year and a half after Gabriel Jara’s October 23, 1925 release from Leavenworth Penitentiary.

Nonetheless, Jara never had the opportunity to hear that recording by Luis Hernández and his friend Leonardo Sifuentes, a corrido attributed to him that captures the disappointment felt by the protagonist at El Paso’s Union Station when both his mother and wife fail to show up to say goodbye to him, his reflections of smuggling, the long train ride to his incarceration at Leavenworth, and the sense of betrayal the penitentiary bound prisoner felt toward his smuggling “friends” who had abandoned him.

Close to one year to the day before Hernández and Sifuentes recorded their influential corrido Gabriel Jara had been dealt one final blow by his involvement with alcohol. On April 3, 1927, in Juarez, Chihuahua, 32-year-old Gabriel Jara, was pronounced dead; Jara’s death certificate cites the cause of death as due to pneumonia and alcoholism.

History does not always act its age, and, when defiant, enjoys coloring outside the lines, expressing indifference towards playing well with others, and has been known to nurture a good enigma. After the research on Gabriel Jara is all written and published, the known evidence yields substance, yet remains circumstantial. Was Jara the sole prisoner from Tom Threepersons’ pitched gun battle or a dupe planted by Customs to save face for the agency after the escape of all of Threepersons’ prisoners? Was Gabriel Jara the composer, or role-model, for the region’s historical smuggling corrido?

Both questions remain open-ended and subject to interpretation.

This is Part Two of a two part story. You can read Part 1 here.

1 “Federal Prisoners Go To Leavenworth,” El Paso Herald, August 7, 1924, p. 10.

2 Salvador Ballinas, “THE VIEW FROM THE SECOND WARD”, Password, The El Paso County Historical Society,

Volume 28, Fall 1983, p. 129.

3 Professor James Nicolopulos, Transcription and Translation, The ROOTS OF THE NARCOCORRIDO, Compact Disc

Booklet, Arhoolie Productions, 2004, p. 16.

4 Bob Chessey, “Ralph Peer’s ‘El Paso Sessions’ of 1929: The Cowgirl and Cowboy Auditions and the Recordings for

Victor Records,” Password, The El Paso County Historical Society, Volume 64, Spring 2020, p. 25.

5 Gabriel Jara #21652; Leavenworth Penitentiary Records, National Archives at Kansas City, Record Group 129,

Records of the Bureau of Prisons, Inmate Case Files, 07/03/1895-06/06/1952; National Archives Identifier 571125.

6 Guillermo E. Hernández, “En busca del autor de “El contraband de El Paso,” Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies,

Volume 30, Number 2, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, October 1, 2005, pp. 139-156 (18).

7 Professor James Nicolopulos & Chris Strachwitz, eds., The ROOTS OF THE NARCOCORRIDO, Compact Disc Booklet,

Arhoolie Productions, 2004, p. 15.

8 El Paso Herald, August 7, 1924, p. 10.

9 Gabriel Jara #21652; Leavenworth Penitentiary Records, National Archives at Kansas City, Record Group 129,

Records of the Bureau of Prisons, Inmate Case Files, 07/03/1895-06/06/1952; National Archives Identifier 571125.

10 Juan Carlos Ramíerez-Pimienta,UNA HISTORIA TEMPRANA DEL CRIMEN ORGANIZADO EN LOS CORRIDOS DE

CIUDAD JUÁREZ, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa/Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, March 2021, pp.43-36.

11 Personal electronic correspondence with author, August 12, 2021.

12 Professor James Nicolopulos, Transcription and Translation, The ROOTS OF THE NARCOCORRIDO, Compact Disc

Booklet, Arhoolie Productions, 2004, p. 16.

A wonderful piece of History.

Great article. Bob did some deep research into both parts of the story.

You get the shoot out in the first part and the music/folklore in the second part.

Well done!