By Kent Paterson

He was the King of Mesa Street, the main drag that winds up and down El Paso’s West Side. He didn’t possess a chunk of pricey real estate, own a trendy new business or have political pretensions. He had no fancy transportation, eschewed plastic money and bank accounts, and frequently had no steady source of income. He was homeless more than once. But he was still the King.

Born Chester Charles Woodward on August 7, 1956, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he was known simply as Chet in El Paso, Texas, where he relocated decades ago. On September 18, 2019, just weeks after celebrating his 63rd birthday, Chet’s life was cruelly ended in an apparent robbery.

The crime occurred yards from his favorite hangout, the Rockin’ Cigar Bar and Grill (RCBG) on Cincinnati Avenue and contiguous to Mesa Street in Kern Place.

“Every day in this bar his name is brought up at least once,” said RCBG owner Frank Ricci Jr. “He had quite a personality,” said Ricci, recalling how he told police investigators that passing time with Chet was like “hanging out with Oscar the Grouch.”

Stabbed near the Stanton Street trolley line, Chet was pronounced dead at the hospital. Though of slight build, he possibly resisted the attack.

“You know my brother, he would never let anyone take what was his,” said his sister Donna Woodward. “He’d put up a fight.”

Last January the El Paso Police Department released a video of a man exiting a store identified as a person of interest in Chet’s killing. More recently, Crime Stoppers’ aired a segment on Chet’s murder. Still, no one has been arrested for the crime. Phone calls to the EPPD for an update were not returned.

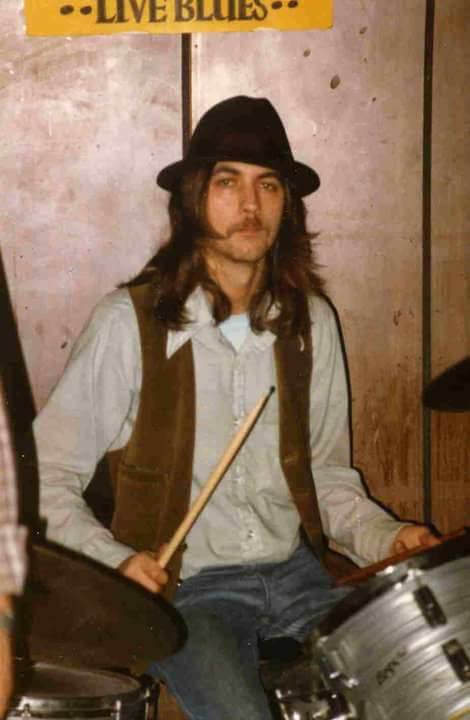

Chet was a rocker and a bluesman who played the drums. He also sang. A performance that sticks in my mind is the husky rendition he did of Otis Redding’s “Sitting by the Dock of the Bay” one karaoke night at Mesa Street’s legendary King’s X bar, where Chet reigned for many, many years.

Although Chet’s lifestyle was antithetical to the 9-5 rat race, he was not your stereotypical “bum.” Mr. Woodward worked off and on as a cellphone troubleshooter at El Paso call centers, and you might have talked with him if you ever had a problem with your phone.

Chet had a creative flair for fashion. He wore furry purple caps and donned striped coats. He styled droopy, floppy and towering hats that made a snazzy match for his long hair. The man sparkled with jewelry, walked in lizard skin boots and pranced around in a pair of patched-up old jeans. His dress was, well, Chetesque.

As Chet’s life unfolded, he acquired a liking for intoxicating substances. Well into his golden years he flirted with LSD and other hallucinogens. But beer was his bread, and his hairy mug could easily have shined on t-shirts blaring the barroom slogan: “Drink beer not water.”

Boastful of his liquid preference, “(Chet) always said he was gonna live forever. He’d be like Keith Richards,” chuckled Ricci.

Chet was a border man long before he arrived in El Paso. Though born in Philadelphia, he was raised just across the Delaware River in Cinnaminson, New Jersey. He spent a good deal of his life dividing time between connected communities and making musical connections that extended downriver to northern Delaware. The King had two extraordinary sisters: Donna, an ex-nun and educator a dozen years older than him, and Margo, ten years his senior.

Chet’s family got its start during World War Two when his father, Chester P. Woodward, was stationed in Philadelphia and met the future bluesman’s mother, Philadelphia native Margaret Mary Smith, at a dance held at the old Normandie Hotel in the University City area of the city.

“My father was in the navy and I guess on weekends the hotel hosted dances for the men,” Donna Woodward reminisced. “My mother was a fantastic dancer, loved dancing more than anything.”

The couple’s three children undertook annual summer trips to Coxsackie, New York, a small community along the Hudson River, where the family visited relatives and savored the local ice cream from a long-established business.

Coxsackie was the occasion to call on Chet’s “amazing’ grandmother, Mary Margaret O’Neill Woodward, daughter of Irish immigrants who married a successful United Fruit Company broker that did a lot of business Central America.

According to Donna, Grandma Woodward was left financially insecure after her husband’s early death because of shady maneuverings by his business partners, forcing the widow to “survive on her wits,” which she did admirably.

A skilled seamstress and the baker of molasses cookies and cranberry cake, as well as a devout Catholic, Grandma Woodward proudly saw her four children earn college scholarships.

“She had big dreams (always wanted to go to Maine and prospect for gold!) but was too poor to have this sort of adventure,” Donna wrote in an email. “Her adventure was managing to raise four children on very little income, ensure they had good educations by virtue of hard work.”

But dreams die hard, and as an elderly woman Grandma Woodward returned to her ancestral homeland of Ireland for the first time since she was 18 years old. On the Emerald Isle, the octogenarian traveled around Galway for a week on horseback accompanied by a trio of twenty-somethings.

Donna likened Grandma Woodward’s physical appearance to the British actress Joan Hickson, who portrayed Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple in a television series- tall hat and elegant suit included.

Experiencing the joy of great grandchildren, Grandma Woodward walked down a hill to catch a bus for Albany and a round of babysitting. She rose early, tended her garden and baked natural coffee cake every Sunday. “Nanny was ‘green’ long before most of us were,” Donna penned.

“Nanny left all of us a great love of adventure and love of reading, and was a role model of service and devotion to family. She especially loved Chet who was the only son of her first-born favorite child.”

During Chet’s childhood, Grandma Woodward hopped aboard a train in Albany for visits in Philly.

Passing away in November 1984, the family matriarch was laid to rest on her 95th birthday.

Chet’s penchant for trains, travel, fashion and adventure- not to mention a spirit of eternal youthfulness- could be glimpsed in Grandma Woodward.

Beamed sister Margo, “(Chet) came from a wonderful family, the Woodwards. He had good genes.”

Young Chet loved collecting things: matchbox cars, stamps, coins, baseball cards, and birdwatching books. Her brother’s musical talents flowering very young, Donna remembered a rambunctious little boy singing Jimmy Rodger’s “Are You Really Mine.”

“He’d wander around the house singing that song,” she continued. “Music was so big and important to Chet. I don’t think it was an intellectual thing; it was deeper.”

By the time he was nine or ten Chet was driving his mom crazy with a new drum set. In the summer of 1968 Donna rendezvoused with Chet and his cousin Joseph in Colorado, loaded the two boys aboard a classy Mercury convertible, and drove them to San Francisco for a life-changing trip.

With plenty of time to explore, Chet and Joseph discovered the old Beat hangout of North Beach and stumbled across Haight Ashbury, the emblematic neighborhood of the ‘60s counterculture that launched psychedelic rock bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Moby Grape.

After the boys got back home, Chet’s mother discovered postcard-sized photos of naked women in their sleeping bags, quite possibly the souvenirs of sex clubs the pair of wide-eyed young cousins may have encountered.

Donna recalled Chet good-naturedly crediting the childhood trip to Baghdad by the Bay for being “responsible for everything I became.” San Francisco remained dear to Chet’s heart for the remainder of his life.

When he was young man and discovering the U.S., the scrappy musician hobnobbed with rock musicians from the Grateful Dead and other icons of the San Francisco sound.

Tragedy struck the Woodward family when Chet’s father Chester, a 1939 Cornell University graduate who had studied physics and engineering and worked in the electronics field, was killed in an automobile accident when his son was only 13 years old. Sadly, Chester Woodward’s own father had passed away when he was just five years old.

According to his sisters, Chet had a very high IQ but struggled with school as a child. The death of his father had a jarring effect on Chet’s behavior, they said. As a young teen he found a safe and stimulating place in the Cinnaminson Alternative School, one of the pedagogical experiments of the 60’s counterculture that offered a creative and self-expressive educational path.

“He started the Catholic school we all went to and didn’t like it,” Donna explained. (Cinnaminson Alternative School) was in the days when education was changed. It had been pretty rigid even when I was growing up.”

Further broadening Chet’s intellectual and aesthetic horizons were the weekend field trips he loved taking to spectacular Cape May, New Jersey, which straddles the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay and is widely considered one of the world’s best spots for birdwatching.

The alternative school ushered in Chet’s coming of age during a time when civil rights movements, SDS, the Vietnam War and the hippie subculture galvanized the nation.

Chet’s worldview was profoundly influenced by such socio-political currents and, most deeply, by the musical explosion of the era.

Chet’s love for the Rolling Stones was so great that he once passed up a summer trip to England so as not to miss the Stones’ U.S. tour, Donna recalled.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, Chet grew a pair of active migratory wings, crisscrossing the U.S. and hitting Canada and Europe as well. He relocated for a spell to South Lake Tahoe near the California-Nevada border, nested on the opposite side of the country in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and flew to wherever the musical flock assembled.

Beginning with his adolescent rock band the Excellos, formed with Cinnaminson buddies, Chet expanded his musical universe. When Donna resided in New York City, she allowed her brother and two friends to crash in her small studio apartment while the aspiring musicians pursued their musical dreams in the Big Apple.

Besides rock n’ roll, he acquired a knack for the blues.

But the percussionist had bills to pay. Dabbling in the Yuppie world, Chet enrolled in a Pennsylvania technical school, got trained in IT and landed a job with the Philadelphia Stock Exchange. Yet the young man’s passions lay with rock and roll and the blues, the rush of the road and the high of nightlife rather than the security of a stable, predictable job.

Gradually, Chet’s musical talent and dedication began hitting high notes. Living along the highly populated Delaware River corridor and just a hop, skip and a jump away from New York, he was well positioned to meet professional musicians and even make a living from the scene.

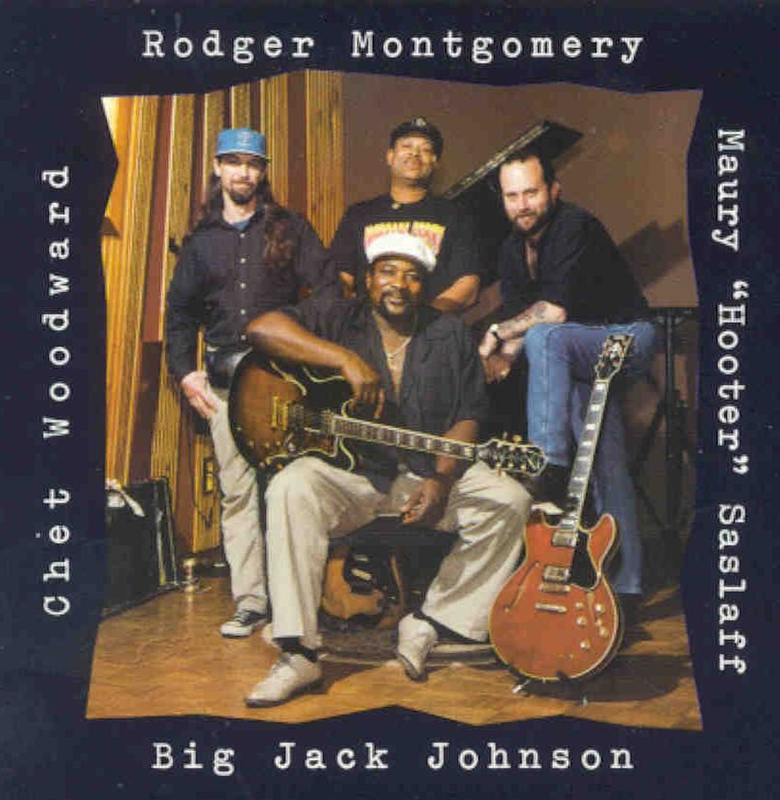

His greatest collaboration was with the African American bluesman Big Jack Johnson. Hailing from the historic blues country and juke joints of northern Mississippi, Johnson was known for his social commentary blues, His songs tackled AIDS, drug abuse, the struggles of family farmers, spousal abuse, and even airline safety. Long largely confined to the Mississippi Delta region because of his family responsibilities, Johnson finally cut loose, hit the road with a vengeance and based himself out of Chet’s Philadelphia stomping grounds for a time.

Prior to his El Paso life, during the mid and late 1990s, Chet toured the U.S, Canada and Europe with Big Jack Johnson and the Oilers. Posting on the Community Gazette, former member Rodger Montgomery described an intense schedule of 300 gigs a year gauged in tens of thousands of miles of burnt rubber on his van.

Before making the transition to a full-time musician, Johnson worked a day job delivering home heating oil for Shell in the Mississippi Delta. Hence, his band’s name “The Oilers.”

In 1997 Big Jack Johnson was the recipient of a prestigious Living Blues magazine award for the best song of 1996, a tune about urban violence called “We Got to Stop This Killin’.” Cited in the Mississippi Folk Life Arts Directory, Johnson was a multiple nominee for a W.C. Handy Award (the Oscar of the blues) before finally winning one (2003) for the best acoustic album, the “Memphis Barbeque Sessions.”

Influenced by country music as well as the blues, Johnson also played the fiddle and the mandolin.

“It’s all mixed up…I just try to reach people’s hearts and make them feel good, and to play something for everybody,” music writer Dave Howell quoted Jackson as declining to narrowly categorize his blues. Ailing, Big Jack Johnson passed away in 2011 in Memphis.

According to Princetoninfo.com, Big Jack Johnson and the Oilers were “sometimes loud, always powerful, raw and gutsy.” That description could apply to Chet’s off-stage demeanor as well.

In his musical heyday Chet also played and recorded with other notable blues performers, including Bluesman Willie and the South Street Runners, a Philadelphia-based blues band that delivered sassy, sexy songs and the accompanying stage-rousing, naughty voice of Yolanda Briggs.

In another musical connection, Reverberation.com credited Chet for tagging the middle nickname of Johnny “Guitar” Edwards, who played with Delaware’s George Thorogood.

Chet’s feverish road life flourished during the blues revival of the 1980s and 1990s. Blues festivals, concerts and clubs were hopping places during those years. From Philadelphia to the San Francisco Bay Area and from Albuquerque to Chicago, the bands toured far and wide while their fans danced in delight and drank it all down.

For Chet and many of his musical contemporaries, the blues highway might not have led to the gold rush, but the tollgates at least allowed them to pay some bills and do what they loved best.

Chet’s oldest sister Donna had little contact with her brother during this time. The former nun landed a job as foreign service officer for the U.S. Department of State in the Philippines and Indonesia, where she almost relocated until the so-called “Asian flu” economic crisis of 1997 dashed her hopes of running a small business. At the same time momentous times were happening in Chet’s life .

Rich Wright, publisher of El Chuqueño and former owner of the old Wildhare’s Booze & Adventure club on Mesa Street, first met Chet when the drummer was on tour with Big Jack Johnson and played Wildhare’s circa 1997. Amazed to see Chet swagger back into the club a month after the gig, Wright queried, “What are you doing?”

Chet had migrated, commencing an El Paso life that contained a good dash of Marty Robbins. In Chet’s life song there was also an alluring chuqueña and the element of tragic love.

“He’d work the door, help out. Mostly work the door,” Wright said of Chet’s presence at Wildhare’s. The former club operator remembers when Chet’s friend was busted in the alley behind Wildhare’s smoking a joint and consequently had a $600 bail bond sitting between him and the hoosegow.

Chet then offered Wright an uncashed paycheck as collateral for the bail money. Agreeing to the exchange, Wright was surprised to see Chet brandish a billfold stuffed with uncashed paychecks.

“He didn’t look like a guy who would have $3,000 in his wallet,” Wright said.

Loyalty was part of the King’s calling card. Although El Paso became his home, Chet the sports fan never stopped rooting for his Philadelphia teams. Donna was impressed with Chet’s “amazing ability to hang on to friends,” some of whom met dated back to childhood.

When Wildhare’s closed in 2003, the once gypsy musician turned El Paso home boy salvaged pieces of the old club’s wall mural and took it home with him next door to the La Posta Motor Lodge, a Mesa Street landmark where he resided for years until a landlord/rent problem landed him on the street.

Years after Wildhare’s closed Wright occasionally bumped into Chet on El Paso’s new trolley system, remembering his last encounter with the King as occurring at the Cincinnati Avenue RCBG two or three months before the murder. A conversation with a third friend present turned to the old Bay Area rock group Moby Grape. “(Chet) knew those guys,” Wright added. Known for their hard driving psychedelic rock, Moby Grape likewise performed a slow song that was one of Chet’s favorites:

“It’s a Beautiful Day Today”

Dawn to dawn a lifetime

The birds sing and day’s begun

The heaven will shine from dawn to dusk

With golden rays of sun

People on their way

Beginning a brand new day

I love (a-)hearing people say

It’s a beautiful day today….

This is Part I of a three part series on Chet Woodward, the King of Mesa Street, by Kent Patterson. You can read Part 2 here. Part 3 is forthcoming.

Hey, that’s going way beyond a journalistic portrait! You are writing a biography? A fascinating person — and family.

And more to come, from Kent Paterson.

Thanks! I don’t like music journalism but this held my attention.

Very Cool story on my husband’s cousin. Chet certainly was interesting.

Dear God RIP Chet. My last thing with him was begging him to stop drinking and start a relationship with Jesus Christ. This was in 2017-2018 when he came back to New Jersey and tried to “get right” but wound up not being able to do so. Chet was a awesome drummer and could play drums with just about anyone! And yes he did give me the name Johnny Guitar Edwards. My middle name being Edward because nobody could pronounce my last name. God Speed to you Chet. I just hope he considered what I said about Jesus. You will be missed.

that was my picture used at the top!!

Chet was something else he was a Bluesman for sure wherever he laid his hat was his home,

We had plenty of battles good and bad we jammed like a mofo when we were playing the Blues

Chet used to yell from his drum throne “we in deep blues now “ I loved him and at times I hated him but he was your brother till the end we shared many a beer and many a shot many doobies and many lines in the year we played together I miss him! RIP my friend you resting with Big Jack now!???????????

Hey Kent, nice job on a tribute to one of the unique friends in my life. I shared many a stage with Chet over the years. I met him in West Chester, Pa. after relocating from New York. Chet was one of a kind that much is for sure. He got me a spot touring with Big Jack Johnson playing guitar. We put a band together that we named “The Lice” after putting a few of us local musicians on stage @ an open mike night @ A bar called “Alibi’s ” in West Chester. Like Johnny “Guitar” Edwards, I tried to get Chet to slow down on the drinking, but he never really slowed down. Well, I suppose a man has got to do what a man has to do and who the hell would I be to judge anyone. In any case, Chet is with Jesus now, and his grandson, and his Dad and Mom, and Jimi and Big Jack and a HUGE host of musicians @ the big jam in the sky. I cannot wait to read part 2 if there is one. BTW, did they ever catch the bastard who took Chet’s life?

Nice read, cousin Chet was great in the oilers, good to have to have him at the house.

Your words were precisely fitting, Rich.

Xo

Angela

Troublemaker

That piece was written by El Chuqueno contributor Kent Paterson.