By Kent Paterson

Standing at the entrance to Ciudad Juárez’s old city hall, Judith Galarza recalled the days of yore when activists like herself were decidedly unwelcome at the imposing stone building that’s perched above the downtown cathedral. How the winds of history have shifted direction.

On the 365th anniversary of the founding of Ciudad Juárez, Galarza had just finished accepting Ciudad Juárez’s prestigious 2024 Fray García de San Francisco Prize on behalf of her human rights organization. The Mexican border city’s highest honor was delivered at a well-attended special session of the Juárez City Council held December 8 in the old city hall.

Named after the founder of Paso del Norte (later Ciudad Juárez) in 1659 and awarded every year during Juárez’s anniversary celebration, the prize is given to individuals and groups named by the municipal government as contributors to peace, justice, human rights, and development in the city.

In her acceptance speech, Galarza, Mexico representative for the Latin American Federation of Family Associations of the Detained and Disappeared (FEDEFAM), evoked the legacy of social and political movements, armed and unarmed, which riveted Mexico from the 1960s to 1980s, but were systematically repressed by all levels of government in the era known as the Dirty War.

“We’ve shown that this struggle is not in vain. We are here, the relatives and survivors of the Dirty War, and thanks to our relatives who had to participate in an armed struggle against a tyranny that was called democracy. They are the important ones,” Galarza said. “We will thank all the recognitions, but it’s for them, our brothers and sisters who sacrificed their lives, their safety and their children to struggle for all the children of Mexico, for a just society so our children will have food, education, culture, sports, like what is happening now.”

Galarza described how the “entire State apparatus” was employed to “annihilate” dissidents and rebels. “They thought they would annihilate them, but they couldn’t because we’re here representing them, those with their arms and us with our political constitution. They will always be in our memory.”

Galarza hails from a Ciudad Juárez family that’s among tens of thousands in Mexico and the Americas which suffered torture, extrajudicial execution, displacement and exile, and forced disappearance during the Dirty War years, an era when U.S.-supported repression stretched from the Rio Grande/Bravo in the north to Tierra del Fuego in the south and into the Caribbean.

Galarza’s sister, Leticia Galarza Campos, enlisted in one of the 20 or so guerrilla groups that loosely formed what’s nowadays known in Mexico as the Armed Socialist Movement.

Active during the 1970s and 1980s, the movement sought to overthrow the one party rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party and effect revolutionary changes. Detained by authorities in Mexico City back in 1978, Leticia remains missing to this day. According to Galarza, her sister was last seen alive a prisoner at the Mexican army’s Camp Number One in Mexico City.

Several truth commissions as well as Mexico’s official National Human Rights Commission have attributed repression, violence and forced disappearances to the Mexican military, state and local police agencies, and civilian government officials. One notorious nationwide force, La Brigada Blanca or the White Brigade, combined military and police personnel.

(For more background, see https://elchuqueno.com/the-storms-and-spirits-of-mexican-september/)

Given the collusion of officials of all stripes in the repression, the 2024 Fray García de San Francisco Prize and December 8 event in Juárez stands as an extraordinary moment in an overdue reckoning that still has a long journey to complete.

Juárez Mayor Cruz Pérez Cuéllar’s remarks at the event touched on a significance transcending generations. Terming FEDEFAM-Mexico a “lighthouse of hope and justice for thousands of families who experienced anguish, pain and uncertainty from the forced disappearance of loved ones during the darkest recent decades of Mexico,” Pérez Cuéllar’s added that the group is struggling “tirelessly not only for truth and memory, but also for justice for all, for those who were victims of violence and repression in the state, as Judith Galarza commented.”

The border mayor continued: “Your struggle hasn’t been only for the disappeared of the Dirty War, but for all the disappeared in the history of Mexico, for all those who continue being invisible because of indifference and forgetfulness.”

In a broad sense, the families who protested the State-conducted violence and forced disappearances during the 1970s and 1980s were the forerunners of organizations and collectives that now proliferate across Mexico. The circumstances and perpetrators of today’s forced disappearances, widely estimated to surpass 100,000, might differ from those of the Dirty War, but the pain, terror and trauma suffered by the victims and their families is hauntingly familiar. Like the activism spawned from the Dirty War, the newer movements are largely led by women.

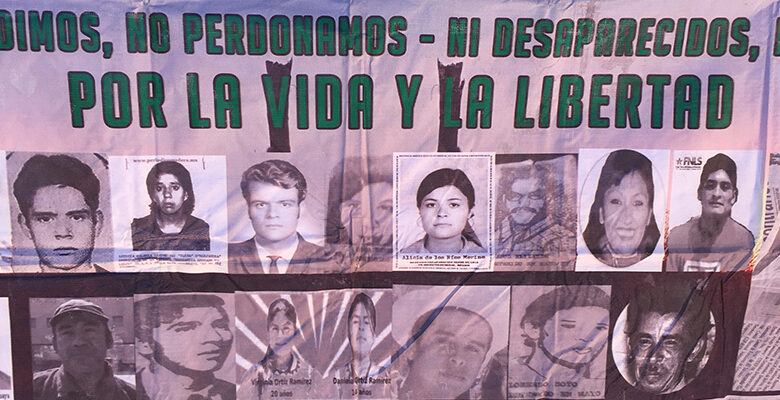

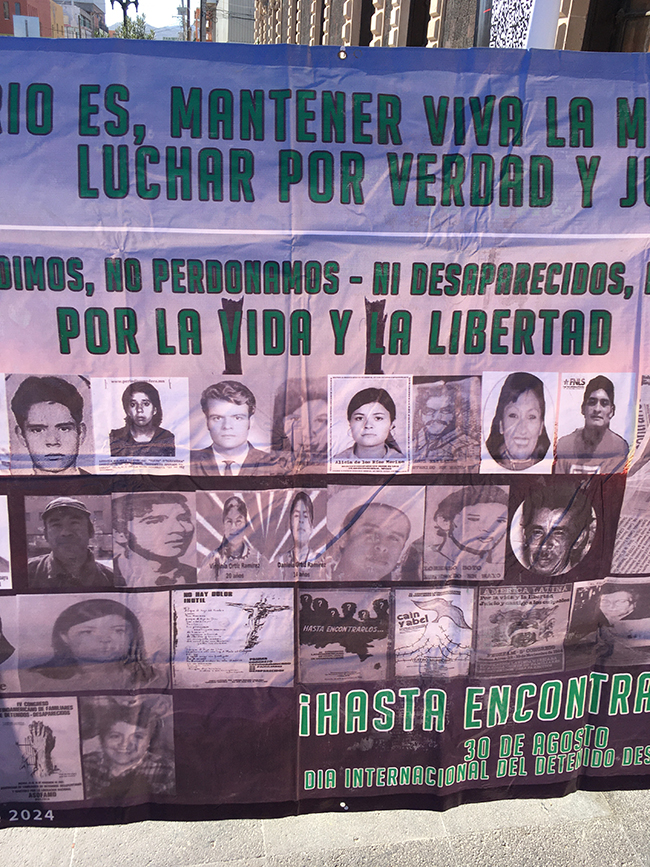

Post-ceremony, FEDEFAM-Mexico and its supporters gathered outside the historic city hall, holding aloof a banner displaying photos of the fallen and disappeared-Leticia Galarza, Alicia de los Ríos Merino and Florencia Soto, among numerous others.

“They weren’t the delinquents or criminals that the repressive government wanted to portray them as through its communications media,” said María Machuca. Victims “were taken away and disappeared. It’s not known were they are, if they live or where they are…”

“We don’t forget, we don’t forgive. We demand truth and justice,” chanted the FEDEFAM contingent, finishing with song:

“We still sing

We still ask

We still dream

We still wait…”

As the former city hall emptied out and streams of holiday shoppers surged into the streets of downtown Juarez on a December day, Galarza reflected further on her group’s long struggle, how the world has changed and how it hasn’t.

“We came here to stone these offices,” Galarza recalled the polarization of decades ago. “(Government officials) closed the doors, the great big door here so we couldn’t break it. We once burned a bus here because they disappeared a student from the Technical Institute of Ciudad Juárez. I remember that his last name was Campos, and they disappeared a worker from the Echeverría Colonia, Antonio Pinedo, but we managed to have them presented alive.”

Galarza elaborated: “There was a heavy confrontation with the authorities. They denied that the White Brigade existed, and that they had detained the disappeared. It was total denial. In reality, our struggle and consistency were the love we had for our brothers and sisters, because they are persons who struggled not individually but collectively for the people, for food, education and housing. At least now we have something with this progressive government.”

Nowadays, FEDEFAM and others are visually altering the urban face of Ciudad Juárez in small but historically meaningful ways. According to Galarza, relatives of the disappeared are placing commemorative plaques on their homes, while Alta Vista high school has done the same to memorialize that institution’s episodes with repression. FEDEFAM-Mexico is proposing that the names of officials responsible for the 20th century repression, such as President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, who presided over the 1968 massacre of student protestors in Mexico City, be removed from public monuments, signage and streets like Díaz Ordaz Viaduct in Ciudad Juárez.

For Galarza and her fellow activists, however, the thrust of their movement is far from symbolic. They look forward to justice from a reinvigorated federal Truth Commission, which was established during the recent López Obrador administration to investigate State crimes against social, political and revolutionary movements and marginalized populations such gays and sex workers between 1965 and 1990.

Galarza said the Truth Commission has made some headway, but uncovering the fates of the disappeared remains the most pending and prickly matter, a task which rattles a complicated Pandora’s Box sealed by a “code of silence” prevailing among surviving perpetrators who could have been trained and advised by the United States, including at the School of the Americas, and other foreign entities.

“If (perpetrators) talk, they’ll have to talk about their sponsors, which was the U.S. government, and all their Israeli, Argentine and gringo advisors.”Many things still remain to be done, but we continue working. “We’re moving ahead until we get truth, justice, wholesale reparation and everything else, and aren’t going to tire and keel over.”

Thanks for sending this out.