By Bob Chessey

This is Part 3 of a three part series. You can read Part 1 here, and Part 2 here.

Valera’s Arrest

The arrest of Ramon Valera is the sole incident that incudes no accusation of Harry personally being involved in selling narcotics. Though Harry Mitchell was never directly implicated, Valera was leaving Mitchell and Fernandez’s bar when followed by Juarez officers.

It is unknown whether Mitchell was disgusted, angry or simply recognized the association was the reality of being partners with the crime boss of Juarez. Regardless, Mitchell chose to remain and benefited from the partnership.

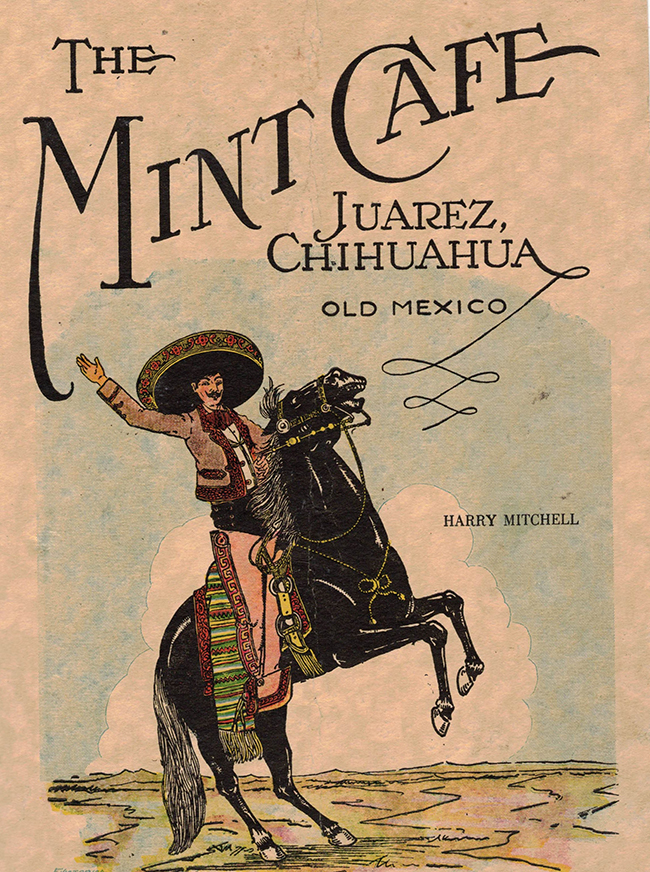

The Valera affair resulted in Harry Mitchell and Enrique Fernandez “terminating” their co-ownership of the Mint. However, at the end the men were in a better business situation than before Valera’s arrest, the pair had regained their legal partnership in the Mint at a bigger and nicer location. In the larger frame, the fallout from the arrest was hardly a set-back.

A sharp contrast in the partnership is illuminating, Mitchell chose to enter and maintain a partnership with Fernandez while he was known to be actively trafficking narcotics into the United States, but terminated the partnership after Enrique’s gunfight with a Mexican Federal officer. Mitchell was likely fearing that he and/or the Mint could face retaliation and retribution from Mexican federal authorities after Fernandez’s violent confrontation with a government agent.

Mitchell’s Arrest for Possession

The arrest of Harry Mitchell occurred two years into the Great Depression. The number of customers and dollars generated by Juarez tourism were plummeting, livelihoods and businesses were at stake in the hospitality sector. Everyone was desperate to financially survive the economic downturn.

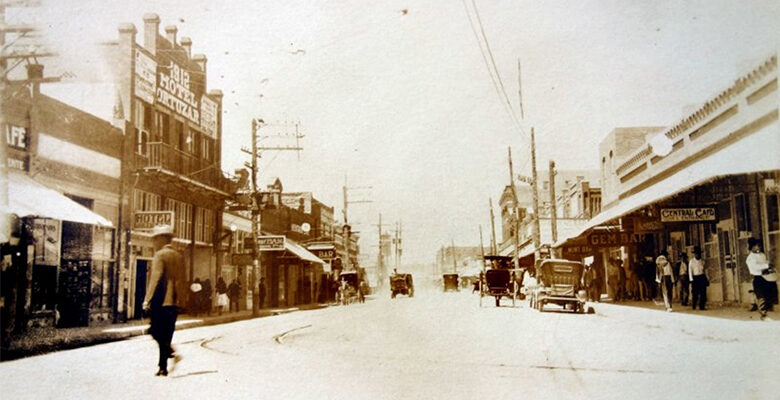

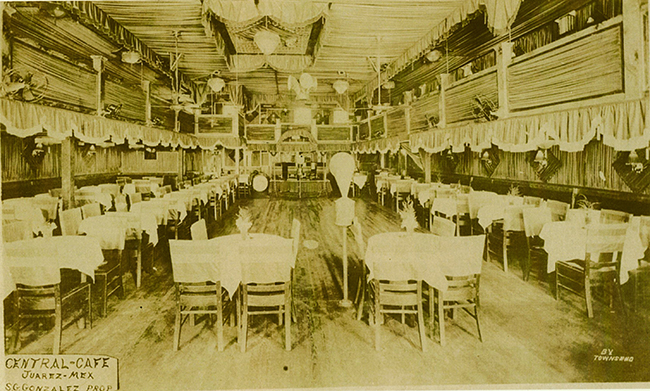

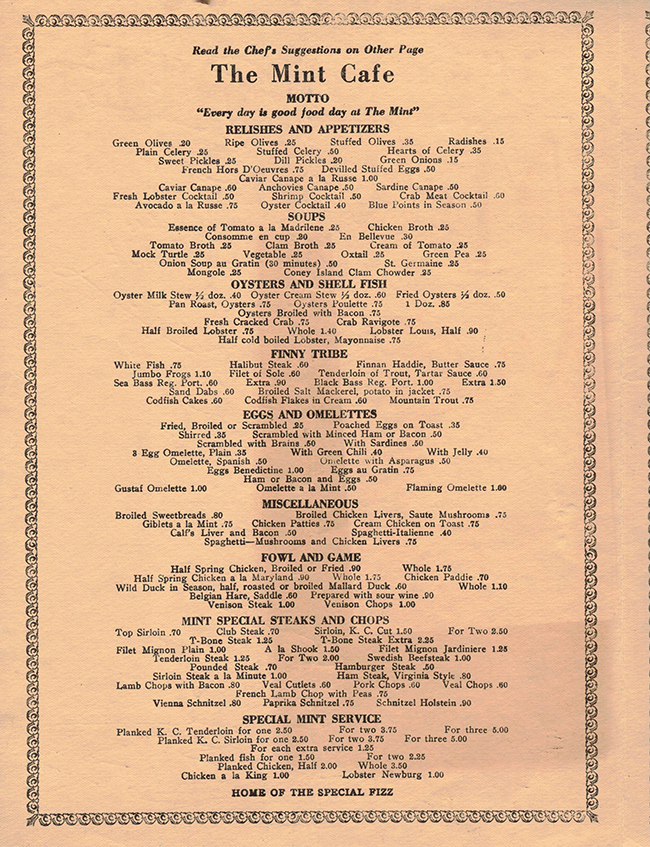

The day before Mitchell and Sanchez’s arrest an El Paso Herald-Post article articulated the financial anxiety and insecurity in Juarez and the fierce competition between the Central Café and the Mint Café, “With the exception of the Central café, opposite the Tivoli, and the Mint café, half way down the block, other cafes and business houses are being ruined. Even the business of these two have fallen off badly.”i

Severo Gonzalez’s rancor against his closest competitor, Mitchell, festered into his swaying, or paying, authorities to antagonize his rival. Unfortunately, there is no record if the acrimony between the two businessmen flared when Mitchell, the Central Café’s manager in 1920, left the management position or if the rift between the restaurateurs developed after the men began competing for customers within two store fronts of each other.

Initially the agitation consisted of fabricating violations regarding the stability and safety of the walls at the Mint Café, but the intimidation rapidly escalated to Mitchell being framed when the Juarez police planted heroin near his seat in Sanchez’s vehicle. The memorandum called attention to the police having “discovered a small packet containing a portion of heroin, but that it was principally composed of bicarbonate and flour.” The diluted dope seemed to be strictly for appearance, only enough heroin was present to make Harry’s alleged possession test positive for the opiate.

The possession ploy was Severo Gonzalez’s desperate attempt, with political backing, including the Governor of Chihuahua, to eliminate his business rival during the throes of the Great Depression. Governor Ortiz continued targeting the Mint after the trafficking charges against Mitchell had been dropped. On Saturday, September 12, 1931 another fire of unknown origin broke out in the basement of the café. On September 28 Governor Ortiz, giving no specific reason, permanently closed the Mint. The Juarez business community viewed the action as an effort to drive business toward the governor’s favored Tivoli gambling hall.ii In return, a percentage would have been expected by Ortiz.

Jose T. Lopez, a businessman from Mexico City who frequently visited Juarez and was concerned that the criminal activities in Juarez would conflict with US and Mexico relations, wrote to the US Ambassador in Mexico documenting his alarm. In his correspondence Lopez explained the background of Governor Ortiz’s actions.

When Andres Ortiz decided to run for Governor of Chihuahua he needed financial backing, and knowing that Fernandez, who at the time was running a gambling house, invested in elections in order to have influence, Ortiz sought, and received, the support of Fernandez. The initial amount bestowed on the future Governor by the crime boss was $25,000 (approx. $464,972 in 2023). But the two men did not remain cordial long. In March, 1931, Ortiz became fearful that he might be removed from office and began traveling frequently to Mexico City to preserve his position and was racking up bills. The worried Governor began leaning on Fernandez for more cash. Ortiz trekked to the well once too many times as Fernandez began refusing to bankroll the Governor’s efforts to remain in office. However, Ortiz succeeded salvaging the governorship and unleashed a vendetta against Fernandez.

In relation to Harry Mitchell’s problem with the Governor, Lopez wrote, “a merciless war is begun (by Ortiz) against Fernandez, even having the building burned in which he had established one of his businesses, the ‘Café Mint.’”iii Clearly, Governor Ortiz and Jose Lopez both believed that Mitchell and Fernandez were still partners. Considering that Mitchell and Fernandez’s partnership was said to have terminated in 1928, three years before the fire, one should assume that the governor would have been informed that the target of his wrath was no longer associated with the Mint Café. Jose Lopez, a frequent visitor to Juarez, believed the men continued being partners or he would have mentioned the termination of the partnership in his letter to the Ambassador.

Both Severo Gonzalez and Governor Ortiz benefited financially from eliminating the Mint Café competition. The following August Severo Gonzalez also assumed management of the Tivoli bar.iv

Despite Governor Ortiz’s order, after repairs from the recent fire, Harry Mitchell reopened the Mint in late November 1931. Taking no chances on another blaze, Mitchell eliminated wood in the restaurant, all walls were concrete and fixtures were metal.v

The blatant harassment of Harry Mitchell, and the flimsy evidence, persuaded the District Attorney to remove himself and pass the case off to a health official who, within three days of their arrest, quickly dropped the charge against Mitchell and Sanchez. Sanchez’s arrest with Mitchell probably complicated the ruse, Rogelio was the brother of a previous Juarez Police Chief.vi

It is doubtful that the British vice-consul would have taken up Mitchell’s ardent defense against his criminal charges; or that the US Consulate would have written a letter of introduction, if they believed that Mitchell was involved in trafficking or selling heroin at the time of his arrest.

Consul Walker’s endorsement of Harry Mitchell as a good character is a startling contrast when juxtaposed against Consul Dye’s 1925 confidential memo accusing Mitchell of being a higher up in the Juarez narcotic trade.

An important difference between the 1925 and 1931 impressions of the US Consul in Juarez is that in 1931 Harry Mitchell had dissolved the partnership almost three years earlier, after Fernandez’s gunfight in the lobby of the Rio Bravo Hotel. Would Mitchell have asked for, or received, a written letter of recommendation if the men had continued the partnership is unknown.

By the fall of 1933 the glory days of Juarez saloons had been atrophied by the crippling 1929 Wall Street market crash and the impending December 5, 1933 repeal of Prohibition. Resilient, Harry Mitchell initiated a new business plan. On November 7, 1933 ground was broken in El Paso to construct a long-held dream, the Harry Mitchell Brewing Company. Mitchell still operated the Mint, but now devoted the majority of his time and attention to the rising brewery plant, often staying at the construction site until two in the morning.vii The Mint, a shadow of its profitable past, would no longer remain his priority.

And so, one would believe, the Mitchell, Fernandez & Mint partnership ended. But a December 23, 1933 El Paso Herald-Post article upends the assumption. A reporter questioned Enrique Fernandez as to why Harry Mitchell, his “partner” in the Mint Café, no longer visited Juarez. In addition, the journalist pursued rumors that Mitchell and he had “split.” Fernandez responded, “There is no mystery to it. Harry is busy with his brewery in El Paso, the Mint is not making any money, and there is no reason why he should work there any more. Neither of us is taking any money from the Mint. We continue to operate it because it is paying the wages of about 40 employes. As for the rumor that Harry is angry at me and does not come to Juarez any more, I’ll say that Harry visited me in Juarez the second day after I was shot (from a gangland assassination attempt) about two weeks ago.”viii

If Mitchell and Fernandez were not partners, why did the reporter go to Juarez and ask Fernandez about his “partner”? If not partners, why did Fernandez answer as though the partnership continued? Fernandez did not deny being partners with, instead, he confirmed that he and Mitchell were currently partners.

In less than one month, January 13, 1934, Fernandez would be murdered, in broad daylight, in the middle of Mexico City.ix

“I was afraid of Fernandez.”

It is not known if Harry Mitchell rationalized and accepted that his and the Mint’s association with Enrique Fernandez’s criminal activities were an occupational hazard of their partnership.

There is a reason Harry Mitchell’s thoughts and feelings regarding Enrique Fernandez are unknown. A 1974 doctoral dissertation examining the prohibition era in El Paso and Juarez reveals Mitchell’s strategy to erase, or at least distance himself, from any involvement and connection with his partner, “Mitchell refused to give interviews to reporters and historians alike. He died in May 1971. A shroud of mystery will remain around the man and many of his former activities.”x

Though not with a historian or reporter, there is one notable exception to Mitchell’s shunning any discussion about Enrique Fernandez. At the end of April, 1935, a suit, brought by El Paso attorney Herman P. Talley on behalf of four Fernandez relatives, was filed in El Paso’s 41st District Court against Harry Mitchell for $19,480.

Enrique Fernandez had no children, but wanted to set up a trust fund providing for the education of two brothers, Benito and Rafael Fernandez, as well as two nephews, Enrique, and Leonardo Fernandez. Eduardo S. Buchoz, administrator of Enrique Fernandez’s estate in El Paso County, claimed to the court that the slain partner had given $19,480 to Mitchell to finance the four men’s education and that the balance had been handed to Mitchell for deposit in a bank.xi

During the trial in June 1936, Mitchell acknowledged signing countless documents at Fernandez request, including the June 11, 1930, receipt for $19,480, but alleged the document was in Spanish and that he had not understood what he was committing to fund.

“I was afraid of Fernandez. He bragged that he had killed a man. I was afraid not to sign,” adding that for several years he constantly feared for his life.xii

Mitchell then informed the court, “I never received the money.”xiii

Despite stating that he never received funds from Fernandez, Mitchell did contribute towards the education of Enrique’s brother Rafael. The brewery owner explained that he aided Rafael so he was able to finish a semester at his school in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Mitchell then implied it was not provided out of obligation, “I would have done as much for any boy.”xiv

Lee L. Henderson, who had been the bookkeeper for the Mint Café, testified that several days after the sale of the Mint he personally brought $25,000 from Juarez to El Paso and deposited the sum in Fernandez’s El Paso bank account. Further damaging the Fernandez estate claim, Henderson corroborated that the Mint’s records do not show that Mitchell was given the $19,480 on the alleged date.

The only comment known to have been recorded of Harry Mitchell speaking about Fernandez’s connection to the underworld occurred during his testimony. When Mitchell was directly asked if Enrique Ferndez was a member of Juarez’s lawless element his ex-partner disingenuously replied, “I don’t know. He never was lawless when he was with me.”xv

Though Harry Mitchell had announced in late November 1928 that he had bought out Enrique Fernandez’s half of the Mint partnership,xvi during the legal proceedings he provided a different version of their partnership’s termination. Under oath Mitchell testified that the men had been equal partners but in 1928 Fernandez had sold his half of the Mint Café to F. O. Mackey for $37,500, and that Fernandez no longer had any connection to the Mint Café.

However, Mitchell informed the court that the two continued to engage in other ventures. Those collaborations consisted of operating the Tivoli gambling casino, but Mitchell claimed that $50,000 vanished from the gambling house and Harry never learned where it disappeared; slot machines; a shoe store where Mitchell invested $10,600, but was never reimbursed or received a return; and a hog selling enterprise.

When Mitchell was pressed about specific other businesses with Fernandez and their dates, Mitchell displayed a selective memory, “Dates mean nothing to me. I’m trying my best to forget Juarez.”xvii

Charged with determining whether Harry Mitchell had received $19,480 to finance Fernandez’s heirs’ education, at the conclusion of the trial the jury only required a thirty-minute deliberation before returning to the jury box with their verdict that Mitchell never received the funds.xviii

It appears that Harry Mitchel could be supple with facts and relate a version convenient to the situation. In November 1928 Mitchell had informed three El Paso newspapers that he had purchased Fernandez’s half interest in the Mint Café. Under oath in 1936 he stated that it was F. O. Mackey who purchased Fernandez’s share of the café.xix

The F. O. Mackey buyout of Fernandez in 1928, followed by Mitchell selling his shares, only to turn around and buy them back, sounds suspiciously like the partners’ 1926 covert maneuverings to regain joint ownership of the Mint after the Valera affair? Is that why and how Enrique Fernandez unexpectedly reappeared in the press as a partner in 1933, as well as in the eyes of Governor Ortiz and Jose Lopez? Were the circular Mint sales intentionally layered to confuse?

Mitchell’s testimony proves their partnership and business dealings were not restricted to the Mint Café, but extended to other joint investments throughout the years. The confirmation of multiple investments with Fernandez begs the question, did Mitchell ever invest in Fernandez’s illegal business ventures, specifically narcotics trafficking?

Summation

The root of Mitchell’s three drug connections, made prior to Fernandez’s partnership in the Mint Café, is US Consul John Dye’s accusation that the Englishman was a “higher-up” in a narcotic’s operation; but provided no proof.

Nonetheless, Harry Mitchell’s name tops the list of Dye’s higher up trafficking suspects. The next two names, though their surname is mistakenly written as Hernandez, are definitely Antonio and Enrique Fernandez. Consul Dye also provided no proof for either brother’s unquestionable participation in narcotic trafficking.

Regardless, Harry Mitchell had a role in Juarez narcotic trafficking during the 1920’s. Harry Mitchell was not naive, or adverse, to how Enrique Fernandez earned his money when he began and continued their partnership. By joining together Mitchell was an enabler, he provided a legal business front and contributed a false sheen of respectability for an active crime boss. Whether or not Harry Mitchell ever personally sold or invested in a single grain of an opiate, the barman benefitted from having a partner who did. Mitchell was able to take advantage of Fernandez’s political “connections” to both Juarez and the state of Chihuahua’s political and law enforcement administrations. One example being the three-card monte shuffling of the Mint’s “ownership,” the selling/ closing then buying/reopening of the cafe after Valera’s arrest, and the probable replay in 1928.

Additionally, the offset to the liability of having Enrique Fernandez as a partner was that some people would have been attracted to patronize a bar owned by a prominent racketeer.

If a different high profile Juarez narcotic trafficker such as Joaquín “Chapo” Guzmán, Ignacia (“La Nacha”) Jaso de Gonzalez, or Amado Carlos (“El Señor de los Cielos”) Fuentes had been a partner with Harry Mitchell would the same courtesy of downplaying or dismissing Mitchell’s partnership with Fernandez be extended?

One can argue that there is reasonable doubt that Harry Mitchell is guilty of involvement in trafficking narcotics; it can just as easily be asserted that there is reasonable doubt of his innocence. Too much time may have elapsed for a definitive answer to be determined. The question of Mitchell’s involvement in narcotic trafficking is inconclusive, spawns more questions than it answers, and only uncovers assumptions and speculation.

This is Part 3 of a three part series. You can read Part 1 here, and Part 2 here.

iBusiness Men Asset Tivoli Hurts Juarez,” El Paso-Herald Post, August 27, 1931, p. 13.

ii“Mint Is Closed,” El Paso Times, September 29, 1931, p. 1.

iiiLopez to Daniels; March 5, 1934; University of Texas Benson Latin American Collection, Internal Affairs 1930-39; Roll 34; pp. 5-6.

iv“Report Tivoli To Be Opened, El Paso Times, July 28, 1932, p. 2; “Llantada To Open Tivoli Wednesday,” El Paso Times, August 1, 1932, p. 8.

v“Mint Café To Have Many New Features,” El Paso Herald-Post, November 25, 1931, p. 14.

viEl Paso Herald-Post, August 28, 1931.

vii“Permit For Brewery Construction Given,” El Paso Herald-Post, November 28, 1933, p.8; “Brewery Now Being Built in El Paso Will Produce 144 McGintys Yearly for Every Resident of City,” El Paso Herald-Post, December 16, 1933, p. 2.

viii“Partner Denies Harry Mitchell Avoids Juarez,” El Paso Herald-Post, December 23, 1933, p. 7.

ix“Enrique Fernandez Shot To Death In Mexico City; General Dies With Him,” El Paso Times, January 14, 1934, p. 1.

xEdward Lonnie Langston, The Impact of Prohibition on the Mexican-United States Border: The El Paso-Ciudad Juarez Case, Doctoral Dissertation, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, 1974, footnote, p. 112.

xi“Harry Mitchell Sued For $43,000,” El Paso Times, May 1, 1935, p. 5; “Evidence Ended In Fund Suit,” El Paso Herald-Post, June 12, 1936, p. 2; “Harry Mitchell Wins Verdict,” El Paso Times, June 13, 1936, p. 16; El Paso Times, June 12, 1936.

xiiEl Paso Herald-Post, June 12, 1936.

xiiiEl Paso Times, June 12, 1936.

xivIbid.

xvEl Paso Times, June 12, 1936.

xviEl Paso Evening Post, November 21, 1928; El Paso Times, November 22, 1928.

xviiEl Paso Times, June 12, 1936.

xviii“Harry Mitchell Wins Verdict,” El Paso Times, June 13, 1936, p. 16; “Mitchell Wins Money Battle,” El Paso Herald-Post, June 13, 1936, p. 2.

xix“El Paso Evening Post, November 21, 1928; Harry Mitchell Now Sole Owner Of Juarez Café, El Paso Herald, November 21, 1928, p.3; Announcement Was Made Yesterday, El Paso Times, November 22, 1928, p. 6.