Zinc Town

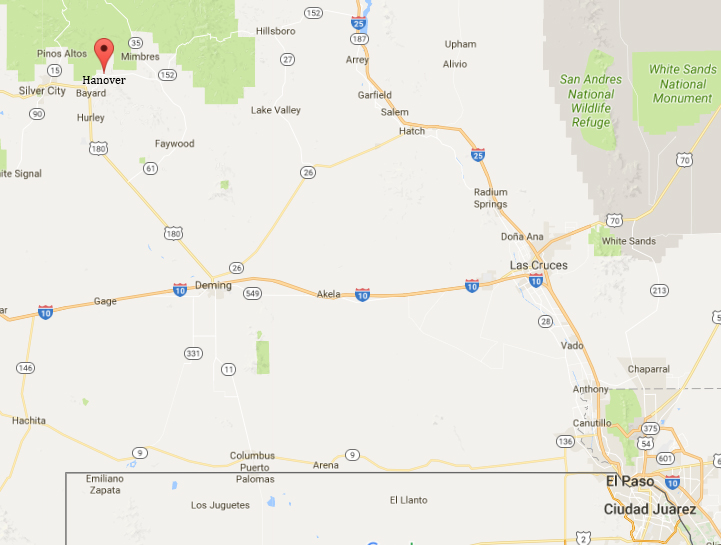

Just three miles southeast of Fierro, New Mexico, the town featured a few weeks ago, is Hanover. Hanover was named by local prospectors for the Hanover Mines near Fierro, which were, in turn, named for Hanover, Germany. Hanover was the hometown of Sofio Henkel/Henkle/Hinkel, who is credited with discovering iron and copper in the area in 1841, but he was forced out by Apaches two years later. More on that story can be found in the initial article on Fierro.

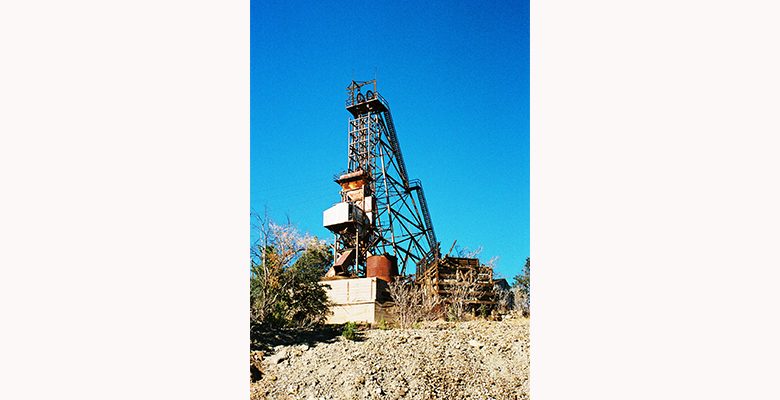

Hanover, however, wasn’t known for copper or iron, but zinc. The post office opened in 1892 and operates to this day, although it has moved a few times from its original location. It’s now in the old railroad depot, beside Hanover Creek. But mining didn’t begin in earnest until decades later, and Hanover still lies in the shadow of the massive Empire Zinc Company headframe (shown above), built during the First World War. From WWI through WWII and on into the Cold War, zinc was Hanover’s bread and butter. But then, in the fall of 1950, things got volatile, bringing outside attention to the remote little town.

(Above is a store and previous location of the Hanover Post Office.)

For some time, Hispanic miners had been angry that the Empire Zinc Company, a subsidiary of the New Jersey Zinc Company, paid Anglos more for doing the same work, officially known as “dual wage rates.” Hispanics were also the only ones given the more dangerous underground duties, and were assigned the lowest quality company housing. So, on October 17, 1950, 140 miners walked off the job. These were members of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (aka Mine Mill), whose leadership was suspected of being communist. Then eight months passed.

On the eighth month the strike got even more intense. That’s when the Empire/New Jersey Zinc Company hired strikebreakers and a federal judge issued a restraining order prohibiting further picketing by miners. At that point, the miners’ wives and children took over picketing. Because they were not miners, this was technically not a violation of the restraining order. It’s said the local sheriff was quickly confronted with a “horde of screaming, singing, chanting women and children.” Sixty-two of these women and children, including a one-month-old baby, were jailed until evening on the first day.

The miners’ families continued picketing for another seven months. One wife of a miner said, “Everybody had a gun, except us. We had knitting needles. We had safety pins. We had straight pins. We had chile peppers. And we had rotten eggs.” The strike ended 15 months after it began, in January 1952, with miners receiving a modest wage increase along with life insurance, health benefits, and hot running water in their company homes.

The whole episode resulted in a movie, “Salt of the Earth,” released in 1954. Hanover’s name was changed to “Zinctown,” and no filming was done in the real Hanover, although some scenes were shot in Fierro. Actual mine workers played roles similar to those they’d had in real life, carrying sidearms to protect themselves while doing so. That’s because the film was written, directed, and produced by members of the Hollywood Ten, a group blacklisted for refusing to testify before the House Un-american Activities Committee (HUAC). So, for many years it was almost impossible to actually see the movie due to its perceived communist associations. Now, of course, it’s not very hard at all. It’s right up there above this paragraph.

It seems a little late in the day to argue about whether communism played a somehow insidious role in the strike in Hanover. Fifteen years later, the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers would merge with the United Steelworkers of America. But you can imagine that in the early 1950’s there was controversy. Nevertheless, in a shady little corner of a rarely-used bridge at the southern end of Hanover, there’s a plaque dedicated by the Board of Grant County Commissioners, Armando D Galindo, Conn W. Brown, and Zeke P. Santa Maria. It reads:

“This bridge is dedicated to the memory of the Mine Mill Women’s Auxiliary of 1951-1952. These brave women took over the picket line against the New Jersey Zinc Co. after their striking husbands were prohibited from picketing by an injunction. They were shot at, tear-gassed, run over and jailed but they stood strong in support of the International Union of Mine Mill and Smelter Workers.”

We can’t leave Hanover and Fierro without a quick mention of Villas Dry Goods Store No. 2, which used the slogan, “Shoes Ready to Wear.” The old false-front sits on a slight rise above Hanover, just before Fierro, in an area that may once have been a separate community known as Union Hill. And where was Villas Dry Goods Store No. 1, you ask? Why, 150 miles away in El Paso, naturally.

As usual, most of what’s in this post was found in “New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns,” “Ghost Towns Alive,” and/or “The Place Names of New Mexico.”

John Mulhouse moved to Albuquerque in 2009 after spending the previous decade in Minnesota, Georgia, Tennessee, and California. He loves the desert, realizes it doesn’t care too much about him, and thinks that’s all as it should be. More of his documentation of the lost, abandoned, beaten, and beautiful can be found at the City of Dust blog and the City of Dust Facebook page.

I remember this. Some of my classmates were taken out of school to walk the plcket line. I remember men with guns and lots of fighting. It was a scary time for us.